The Conversation

Australia emits mercury at double the global average

A report released this week by advocacy group Environmental Justice Australia presents a confronting analysis of toxic emissions from Australia’s coal-fired power plants.

The report, which investigated pollutants including fine particles, nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, also highlights our deeply inadequate mercury emissions regulations. In New South Wales the mercury emissions limit is 666 times the US limits, and in Victoria there is no specific mercury limit at all.

This is particularly timely, given that yesterday the Minamata Convention, a United Nations treaty limiting the production and use of mercury, entered into force. Coal-fired power stations and some metal manufacturing are major sources of mercury in our atmosphere, and Australia’s per capita mercury emissions are roughly double the global average.

Read more: Why won’t Australia ratify an international deal to cut mercury pollution?

In fact, Australia is the world’s sixteenth-largest emitter of mercury, and while our government has signed the Minamata convention it has yet to ratify it. According to a 2016 draft impact statement from the Department of Environment and Energy:

Australia’s mercury pollution occurs despite existing regulatory controls, partly because State and Territory laws limit the concentration of mercury in emissions to air […] but there are few incentives to reduce the absolute level of current emissions and releases over time.

Mercury can also enter the atmosphere when biomass is burned (either naturally or by people), but electricity generation and non-ferrous (without iron) metal manufacturing are the major sources of mercury to air in Australia. Electricity generation accounted for 2.8 tonnes of the roughly 18 tonnes emitted in 2015-16.

Mercury in the food webMercury is a global pollutant: no matter where it’s emitted, it spreads easily around the world through the atmosphere. In its vaporised form, mercury is largely inert, although inhaling large quantities carries serious health risks. But the health problems really start when mercury enters the food web.

I’ve been involved in research that investigates how mercury moves from the air into the food web of the Southern Ocean. The key is Antartica’s sea ice. Sea salt contains bromine, which builds up on the ice over winter. In spring, when the sun returns, large amounts of bromine is released to the atmosphere and causes dramatically named “bromine explosion events”.

Essentially, very reactive bromine oxide is formed, which then reacts with the elemental mercury in the air. The mercury is then deposited onto the sea ice and ocean, where microbes interact with it, returning some to the atmosphere and methylating the rest.

Once mercury is methylated it can bioaccumulate, and moves up the food chain to apex predators such as tuna – and thence to humans.

As noted by the Australian government in its final impact statement for the Minamata Convention:

Mercury can cause a range of adverse health impacts which include; cognitive impairment (mild mental retardation), permanent damage to the central nervous system, kidney and heart disease, infertility, and respiratory, digestive and immune problems. It is strongly advised that pregnant women, infants, and children in particular avoid exposure.

Read more: Climate change set to increase air pollution deaths by hundreds of thousands

Australia must do betterA major 2009 study estimated that reducing global mercury emissions would carry an economic benefit of between US$1.8 billion and US$2.22 billion (in 2005 dollars). Since then, the US, the European Union and China have begun using the best available technology to reduce their mercury emissions, but Australia remains far behind.

But it doesn’t have to be. Methods like sulfur scrubbing, which remove fine particles and sulfur dioxide, also can capture mercury. Simply limiting sulfur pollutants of our power stations can dramatically reduce mercury levels.

Ratifying the Minamata Convention will mean the federal government must create a plan to reduce our mercury emissions, with significant health and economic benefits. And because mercury travels around the world, action from Australia wouldn’t just help our region: it would be for the global good.

In an earlier version of this article the standfirst referenced a 2006 study stating Australia is the fifth largest global emitter of mercury. Australia is now 16th globally.

Robyn Schofield received a Australian Antarctic Science Grant to research mercury in Antartica, and currently receives an ARC Discovery Grant. Robyn is a member of the Clean Air and Urban Landscape Hub.

Costly signals needed to deliver inconvenient truth

Former US Vice President and Chair of the Climate Reality Project Al Gore and Victoria's climate and energy minister Lily D'Ambrosio (right) ride on a tram after speaking at the climate conference in Melbourne. AAP/Tracey Nearmy, CC BY-ND

Former US Vice President and Chair of the Climate Reality Project Al Gore and Victoria's climate and energy minister Lily D'Ambrosio (right) ride on a tram after speaking at the climate conference in Melbourne. AAP/Tracey Nearmy, CC BY-NDA little over half the world’s population sees climate change as a serious problem (54% according to a 40-nation Pew Research survey). Coincidentally, roughly the same number identify as Christian or Muslim (55%).

On the one hand, these statistics speak to the success of climate change communication. In just a few decades, climate scientists have convinced a large part of the world’s population that a set of powerful, invisible forces have important implications for the way we live. World religions took centuries to achieve similar success.

On the other hand, religion spreads without the support of empirical evidence and is capable of generating changes in people’s behaviour that climate scientists would envy. Religion pervades almost every aspect of the lives of believers, from the food they eat to what they do on the weekend. We argue that scientists can take lessons from this.

Actions louder than wordsOne way that religions succeed is to focus not just on what adherents say, but what they do. A key strategy is to encourage or require adherents (including leaders) to engage in behaviours that act as signals of commitment to their beliefs. Followers, for example, may be asked to dress in distinctive (often impractical) garb, engage in regular rituals in public (sometimes multiple times a day), or abide by seemingly arbitrary dietary restrictions.

Even more is required of leaders, from highly restricted diets, giving up worldly possessions, to lives of celibacy. The costs of these behaviours make them hard-to-fake signals of sincerity that help spread belief to otherwise sceptical outsiders and bolster support among followers.

We like to think that science is completely different. While religion is dogmatic and based on faith, science is continually questioning, grounded in the scientific method and the many useful predictions and technologies that emerge from it.

But we do not, as individuals, test all the claims that scientists and science communicators make. Out of practical necessity, we must all take a good deal of what science tells us, as well as it’s implications for how we should live our lives, on trust.

Sending signals of commitmentAl Gore’s 2006 movie An Inconvenient Truth was hailed as a turning point in public awareness of climate change, but it also attracted heated criticism. Some criticism was directed at the movie’s content, but much was also made of Gore’s apparent hypocrisy, including his use of private jets, home energy consumption and acquisition of beachfront property.

While ad hominem attacks do not undermine the factual claims made in the movie, Gore’s actions undoubtedly reduced the credibility of his message to some people. If he is still flying extensively and buying up beachfront property, how bad can the problem really be?

We argue that because all of us, scientists and non-scientists alike, must take much in science on trust, behavioural signals are potentially just as important to the spread of scientific knowledge as they are to that of religion. It does not follow that science and religion stand on the same epistemological foundations; rather it is an acknowledgement that trust in the vast stocks of scientific knowledge and its implications can only be established by any one individual using non-scientific means.

Going beyond talkScientists and science communicators should therefore be prepared to make better use of signals, particularly costly signals, to demonstrate they are truly committed to what they are advocating.

Whether or not An Inconvenient Truth was undermined by apparent hypocrisy, it was a lost opportunity on Gore’s part. If, for example, he had sold his energy-intensive mansion and refused to fly to his engagements, he could have sent a credible signal to the public that he was personally deeply concerned about the threat of climate change. As his new movie, An Inconvenient Sequel, is released around the world, he has another opportunity to bolster his argument with action.

We do not wish to lambast leading climate change communicators for hypocrisy. There are plenty of others who do that already. But our point is this: although the validity of scientific ideas should be independent of their messenger, our actions matter for generating the kind of deep commitment to scientific evidence that will be required to tackle the problems of our time. Scientists and science communicators need to focus not just on what we say, but on the signals we send via our actions.

Our personal action planOur own first step in this direction is a commitment to forgo air travel in 2018 as a costly signal of our belief in the need for urgent action on climate change. By far our largest contribution to greenhouse gas emissions is flying to academic conferences. A single return flight from Auckland to London is roughly equivalent to the average annual carbon dioxide emissions per capita of New Zealand.

Carbon offsets are one way to address emissions from flying, but (efficacy aside) they are controversial and tend to be cheap and invisible, which makes them ineffective as credible signals of commitment.

We make our commitment to forgo flying publicly and challenge other senior academics to do likewise. Forgoing flying, particularly for those in New Zealand and Australia, carries costs in that networking and exposure to new ideas can become more difficult. Giving a speech at an international conference is highly prestigious for an academic, and in New Zealand it is one of the criteria in our national research assessment exercise.

With careful planning, we believe we can overcome some of the costs in forgoing opportunities to travel. We intend to make better use of prerecorded talks and video conferencing and support local and online conferences and research networks. By committing to these practices, and encouraging others to do the same, scientists can demonstrate that change is possible and send a powerful signal that they are personally committed to action on climate change.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Climate change is a financial risk, according to a lawsuit against the CBA

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia has been in the headlines lately for all the wrong reasons. Beyond money-laundering allegations and the announcement that CEO Ian Narev will retire early, the CBA is now also being sued in the Australian Federal Court for misleading shareholders over the risks climate change poses to their business interests.

This case is the first in the world to pursue a bank over failing to report climate change risks. However, it’s building on a trend of similar actions against energy companies in the United States and United Kingdom.

Read more: Why badly behaving bankers will never fear jail time

The CBA case was filed on August 8, 2017 by advocacy group Environmental Justice Australia on behalf of two longstanding Commonwealth Bank shareholders. The case argues that climate change creates material financial risks to the bank, its business and customers, and they failed in their duty to disclose those risks to investors.

This represents an important shift. Conventionally, climate change has been treated by reporting companies merely as a matter of corporate social responsibility; now it’s affecting the financial bottom line.

What do banks need to disclose?When banks invest in projects or lend money to businesses, they have an obligation to investigate and report to shareholders potential problems that may prevent financial success. (Opening a resort in a war zone, for example, is not an attractive proposition.)

However, banks may now have to take into account the risks posed by climate change. Australia’s top four banks are heavily involved in fossil-fuel intensive projects, but as the world moves towards renewable energy those projects may begin to look dubious.

Read more: How companies are getting smart about climate change

As the G20’s Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures recently reported, climate risks can be physical (for instance, when extreme weather events affect property or business operations) or transition risks (the effect of new laws and policies designed to mitigate climate change, or market changes as economies transition to renewable and low-emission technology).

For example, restrictions on coal mining may result in these assets being “stranded,” meaning they become liabilities rather than assets on company balance sheets. Similarly, the rise of renewable energy may reduce the life span, and consequently the value, of conventional power generation assets.

Companies who rely on the exploitation of fossil fuels face increasing transition risks. So too do the banks that lend money to, and invest in, these projects. It is these types of risks that are at issue in the case against CBA.

What did the CBA know about climate risk?The claim filed by the CBA shareholders alleges the bank has contravened two central provisions of the Corporations Act 2001:

companies must include a financial report within the annual report which gives a “true and fair” view of its financial position and performance, and

companies must include a director’s report that allows shareholders to make an “informed assessment” of the company’s operations, financial position, business strategies and prospects.

The shareholders argue that the CBA knew – or ought to have known – that climate-related risks could seriously disrupt the bank’s performance. Therefore, investors should have been told the CBA’s strategies for managing those risks so they could make an informed decision about their investment.

Read more: We need a Royal Commission into the banks

The claim also zeros in on the lengthy speculation over whether the CBA would finance the controversial Adani Carmichael coal mine in Queensland. (The bank has since ruled out financing the mine.) The shareholders assert that the resulting “controversy and concern” was a major risk to the CBA’s business.

Global litigation trendsWhile the CBA case represents the first time worldwide that a financial institution has been sued for misleading disclosure of climate risk, the litigation builds on a broader global trend. There have been a number of recent legal actions in the United States, seeking to enforce corporate risk disclosure obligations in relation to climate change:

Energy giant Exxon Mobile is currently under investigation by the Attorneys General of New York and California over the company’s disclosure practices. At the same time, an ongoing shareholder class action alleges that Exxon Mobile failed to disclose internal reports about the risks climate change posed to their oil and gas reserves, and valued those assets artificially high.

Similar pathways are being pursued in the UK, where regulatory complaints have been made about the failure of major oil and gas companies SOCO International and Cairn Energy to disclose climate-related risks, as required by law.

In this context, the CBA case represents a widening of litigation options to include banks, as well as energy companies. It is also the first attempt in Australia to use the courts to clarify how public listed companies should disclose climate risks in their annual reports.

Potential for more litigationThis global trend suggests more companies are likely to face these kinds of lawsuits in the future. Eminent barrister Noel Hutley noted in October 2016 that many prominent Australian companies, including banks that lend to major fossil fuel businesses, are not adequately disclosing climate change risks.

Hutley predicted that it’s likely only a matter of time before we see a company director sued for failing to perceive or react to a forseeable climate-related risk. The CBA case is the first step towards such litigation.

Anita Foerster receives support from Australian Research Council Discovery Project – DP 160100225, ‘Developing a Legal Blueprint for Corporate Energy Transition’.

Jacqueline Peel receives support from Australian Research Council Discovery Project – DP 160100225, ‘Developing a Legal Blueprint for Corporate Energy Transition’.

'Smart home' gadgets promise to cut power bills but many lie idle – or can even boost energy use

Cutting energy use takes more than just the flick of a smartphone. 3dfoto/shutterstock.com

Cutting energy use takes more than just the flick of a smartphone. 3dfoto/shutterstock.com“Smart” home control devices promise to do many things, including helping households reduce their energy bills.

Devices such as “connected” lightbulbs and smart plugs let you operate or automate lights and other appliances from your smartphone, and are widely available from major retailers and online.

They are one of many innovative technologies advocated by the energy sector, and the recent Finkel Review of the energy market, to help consumers manage their energy use.

However, our research published today suggests that these devices are not the “easy” answer to energy management. In our trial, we found that households can use them in ways that increase energy use rather than reduce it, and that many people find them too complicated to get up and running.

Read more: Dream homes of the future still stuck in the past.

Smart home techs on trialIn our study, funded by Energy Consumers Australia, we supplied 46 volunteer households in Victoria and South Australia with a couple of market-leading smart control devices to try out. We made sure we included a broad range of households – not just tech-savvy, early adopter types.

The results were surprising. A quarter of the households didn’t even attempt to install the devices; another quarter tried but failed to install them, and a further quarter successfully installed them but then abandoned them because they were considered inconvenient or not useful.

That left one quarter who were actively using the devices on an ongoing basis.

Unsuccessful installations weren’t just thwarted by the devices themselves or by a lack of persistence or knowledge. Householders who tried but gave up on the devices did so for a range of reasons, including smartphone compatibility issues, unreliable WiFi or Internet access, forgotten passwords, device app problems including recurring error messages, and concern over requests to hand over personal information.

Who used the devices?The people most likely to successfully set up and continue using the devices were technology enthusiasts – and most often male. This is consistent with previous studies which have found that men are more likely to be interested in home automation.

Older users in particular can struggle with smart home technology.

Author provided

Older users in particular can struggle with smart home technology.

Author provided

Energy-vulnerable households (those at higher risk of difficulty paying energy bills) were more interested in the devices than “regular” households, possibly because they placed greater value on the promised energy savings, or had more time to persist with the installation process. However, energy-vulnerable households are less likely to have the necessary technology infrastructure to use smart home control devices successfully, such as high-end smartphones and fast, reliable home internet connection.

Older participants in our study (those over 55) rarely used the devices. Households with children were concerned about the entry of more digital technology into their lives. Smart home control can also be inconvenient if some occupants continue to use the manual switches on lights or appliances (such as children without their own smartphones), as this can deactivate smart control for the rest of the household.

Lifestyle improvements beat energy savingsThe households we interviewed were very interested in the potential for smart home control to improve their lifestyles, through improved security and safety, better comfort, conveniences such as turning lights off from bed, and aesthetic features such as “mood lighting”.

Yet while our study did not measure energy consumption, it was clear from the results that the ways households were using (or wanted to use) their devices could both decrease and increase energy consumption.

While some households reduced the operating time of lights or small appliances, others used smart control to increase their operating time, for instance by switching their heater on before getting home.

Pre-heating or pre-cooling homes, or running appliances when not at home to give the house a “lived-in” look intended to deter burglars, can be beneficial for health, comfort or well-being but can also increase energy consumption.

Tellingly, no household in our study used their smart devices to shift the timing of their energy use, even though most said their electricity rates were cheaper at night. When asked if smart plugs could help shift energy use to off-peak periods, many respondents said they did not see these devices as a necessary or convenient way to do it. They were more interested in simple timers and automation functions on the appliances themselves.

Doing more with smart home controlSix of the 46 households involved in our trial said they were interested in doing more with smart home control. However, they were mainly interested in lifestyle improvements rather than saving energy. This is consistent with the way these products are being marketed to households by technology companies.

Our findings are also consistent with another recent trial of smart home technologies in the UK. That study found that participants made either limited or no use of similar devices to manage their energy use. Like us, the research team raised concerns about the potential for smart control to generate new forms of energy demand.

Read more: Slash Australians’ power bills by beheading a duck at night.

These findings call for more caution in how smart home control is promoted by the energy sector. We need to be realistic about how these products are marketed, how the media influences the way the products are used, and how the other benefits of smart home control may affect home energy consumption.

The extent of technical and usability issues also needs to be acknowledged. There is a real risk that householders could spend considerable time and money on devices that don’t deliver energy savings. The devices are not equally accessible for everyone, and older users in particular might need help in using them effectively.

The danger is in assuming that lower power bills can come neatly packaged in a box – the reality, as always, is more complicated.

Yolande Strengers receives funding from the Australian Research Council, Energy Consumers Australia, electricity utilities and consumer advocacy organisations. She is a member of the Australian Sociological Association (TASA).

Larissa Nicholls receives funding from Energy Consumers Australia and Victorian Council of Social Service. She also works on projects funded by the Australian Research Council and electricity utilities. She is a member of the non-profit organisations, Alternative Technology Association and the European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ECEEE).

Tweet streams: how social media can help keep tabs on ecosystems' health

Social media posts, such as this image uploaded to Flickr, can be repurposed for reef health monitoring. Sarah Ackerman/Flickr/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Social media posts, such as this image uploaded to Flickr, can be repurposed for reef health monitoring. Sarah Ackerman/Flickr/Wikimedia Commons, CC BYSocial media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram could be a rich source of free information for scientists tasked with monitoring the health of coral reefs and other environmental assets, our new research suggests.

Ecosystems are under pressure all over the world, and monitoring their health is crucial. But scientific monitoring is very expensive, requiring a great deal of expertise, sophisticated instruments, and detailed analysis, often in specialised laboratories.

This expense – and the need to educate and engage the public – have helped to fuel the rise of citizen science, in which non-specialist members of the public help to make observations and compile data.

Our research suggests that the wealth of information posted on social media could be tapped in a similar way. Think of it as citizen science by people who don’t even realise they’re citizen scientists.

Read more: Feeling helpless about the Great Barrier Reef? Here’s one way you can help.

Smartphones and mobile internet connections have made it much easier for citizens to help gather scientific information. Examples of environmental monitoring apps include WilddogScan, Marine Debris Tracker, OakMapper and Journey North, which monitors the movements of Monarch butterflies.

Meanwhile, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Flickr host vast amounts of information. While not posted explicitly for environmental monitoring, social media posts from a place like the Great Barrier Reef can contain useful information about the health (or otherwise) of the environment there.

Picture of health? You can learn a lot from holiday snaps posted online.

Paul Holloway/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Picture of health? You can learn a lot from holiday snaps posted online.

Paul Holloway/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Twitter is a good resource for this type of “human sensing”, because data are freely available and the short posts are relatively easy to process. This approach could be particularly promising for popular places that are visited by many people.

In our research project, we downloaded almost 300,000 tweets posted from the Great Barrier Reef between July 1, 2016 and March 17, 2017.

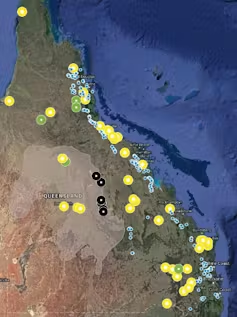

After filtering for relevant keywords such as “fish”, “coral”, “turtle” or “bleach”, we cut this down to 13,344 potentially useful tweets. Some 61% of these tweets had geographic coordinates that allow spatial analysis. The heat map below shows the distribution of our tweets across the region.

Tweet heat map for the Great Barrier Reef.

Author provided

Tweet heat map for the Great Barrier Reef.

Author provided

Twitter is known as place for sharing instantaneous opinions, perceptions and experiences. It is therefore reasonable to assume that if someone posts a tweet about the Great Barrier Reef from Cairns they are talking about a nearby part of the reef, so we can use the tweet’s geocoordinates as indicators of the broad geographic area to which the post is referring. Images associated with such tweets would help to verify this assumption.

Our analysis provides several interesting insights. First, keyword frequencies highlight what aspects of the Great Barrier Reef are most talked about, including activities such as diving (876 mentions of “dive” or “diving”, and 300 of “scuba”), features such as “beaches” (2,909 times), and favoured species such as “coral” (434) and “turtles” (378).

The tweets also reveal what is not talked about. For example, the word “bleach” appeared in only 94 of our sampled tweets. Furthermore, our results highlighted what aspects of the Great Barrier Reef people are most happy with, for example sailing and snorkelling, and which elements had negative connotations (such as the number of tweets expressing concern about dugong populations).

Casting the net widerClearly, this pool of data was large enough to undertake some interesting analysis. But generally speaking, the findings are more reflective of people’s experiences than of specific aspects of the environment’s health.

The quality of tweet information with regard to relevant incidents or changes could, however, be improved over time, for example with the help of a designated hashtag system that invites people to post their specific observations.

Read more: Survey: two-thirds of Great Barrier Reef tourists want to ‘see it before it’s gone’.

Similar alert systems and hashtags have been developed for extreme events and emergency situations, for example by the New South Wales Fire Service.

Tweets also often contain photographs – as do Instagram and Flickr posts – which can carry useful information. An image-based system, particularly in cases where photos carry time and location stamps, would help to address the lack of expertise of the person posting the image, because scientists can analyse and interpret the raw images themselves.

The Great Barrier Reef is, of course, already extensively monitored. But social media monitoring could be particularly beneficial in countries where more professional monitoring is unaffordable. Popular destinations in the Pacific or Southeast Asia, for example, could tap into social media to establish systems that simultaneously track visitors’ experiences as well as the health of the environment.

While it is early days and more proof-of-concept research is needed, the technological possibilities of Big Data, machine learning and Artificial Intelligence will almost certainly make socially shared content a useful data source for a wide range of environmental monitoring in the future.

Susanne Becken receives funding from National Environmental Science Program. She is a member of the Pacific Asia Travel Association's Sustainability and Social Responsibility committee.

Bela Stantic receives funding from receives funding from National Environmental Science Program.

Rod Connolly receives funding from National Environmental Science Program and Australian Research Council.

People, palm oil, pulp and planet: four perspectives on Indonesia's fire-stricken peatlands

Peat means different things to different people. To many Irish people, it means fuel. To the Scottish, it adds a smoky flavour to their whisky. Indonesia’s peatlands, meanwhile, are widely known as the home of orangutans, the palm oil industry, and the persistent fires that cause the infamous Southeast Asian haze.

Indonesians, and other people with ties to these peatlands, have a range of perspectives on the value of peat – both commercial and otherwise.

Here we explore them through the eyes of four fictitious but representative characters.

Read more: How plywood started the destruction of Indonesia’s forests.

The smallholder in rural SumatraPeatland is my land. As migrants from Java, my family now have our own house and our own crops. In some years there have been terrible fires, with smoke so thick we can’t even see the end of our street, and all of our food crops burn. But in other years, the rice and corn grow well, my family eat fish every day, my wife smiles, and our children grow tall.

In Java we had no land of our own, and I worked as a farm labourer. Here in Sumatra we have our own peatland. It is different from Javanese soil but we work hard to tend our crops, watering them in the dry season and protecting them from fire.

A big palm oil company has trained me and 50 other men from our village in firefighting. We have uniforms and water-holding backpacks, and I have learned about when the fire will come. They are helping us to protect our palms, and their own palms, of course. My palms are still young, but in a few years I will sell the palm oil fruit to the company, and then my boys can go to high school in town – as long as the palms don’t burn, God willing.

Floods are a harder problem. How can I protect my land? The government dug canals to drain the peatland before we came, but they are not big enough to hold all the water that comes from the heavens and the floods come more and more often.

The official in JakartaPeatland is our burden. Indonesia has fertile land, rich oceans… and then there are the peatlands. It is always either too wet to use, or so dry that it burns.

Other Southeast Asian governments want us to end the fires and haze single-handed, but Indonesia isn’t the only one to blame; peatland fires are a regional problem.

We are caught between domestic and international pressures. Develop our peatlands to lift our people out of poverty, or preserve them for orangutans and carbon storage. Of course, the Indonesian people are my priority.

When I studied agriculture at university in Brisbane in the 1990s, my classmates were a little fuzzy about where Indonesia is, let alone what happens here. Now, when our ministry visits Canberra, I feel sad to see “Palm Oil Free” displayed prominently on supermarket products. Westerners don’t understand that not all palm oil is grown on peatlands, that it is a healthy oil and a highly efficient crop perfectly suited to tropical conditions.

Oil palms can be grown sustainably and have helped many farmers out of poverty. Nearly half of Indonesia’s palm oil is sourced from smallholders, and losing that income can really hurt them.

A palm growing on peatland.

Andri Thomas, Author provided

A palm growing on peatland.

Andri Thomas, Author provided

Our ministry is working hard to ensure that Indonesia develops our peatlands sustainably, restoring and rewetting degraded areas and working with the local people to find economic uses for wet peat. My son wants to follow in my footsteps and work on peatlands too, and has applied to study sustainable development at university in Singapore.

So while peatlands are currently a source of national embarrassment, many minds are focused on transforming them into the goose that lays the golden egg for Indonesia.

Read more: Sustainable palm oil must consider people too.

The businessperson in SingaporePeatland is good, profitable land. For too long we have considered it wasteland – too wet, too far away. But technology from peat-rich countries like Finland and Canada is helping us to use tropical peatlands for people.

My pulp and paper company has half of its plantations on peatlands, which produce more than a third of our pulpwood. My silviculture (forest management) team works closely with my environmental manager and PR team to ensure that our plantations are grown according to best practice, and that our shareholders and clients know it.

The community benefits in the regions around our plantations are easy to see. The village that my parents came from has electricity now, and big modern houses have replaced the old wooden ones. We have paved the road and our taxes support the government’s new health centre and primary school.

We are not a big company like Asia Pulp and Paper, which can afford to retire part of the estate on peatlands, but we do try to abide by the 2011 moratorium on new plantations on peatlands, despite repeated scepticism from environmental groups. Anyway, the moratorium is a Presidential Instruction, and so is flexibly applied.

The Indonesian government doesn’t want any more fires, and neither do we – we don’t want our plantations to burn! But the new regulations that require rewetting the peat are a big challenge for us. What will grow in wet peatland?

I lie awake at night worrying about my company’s future. What species can we diversify into? Should we move away from pulp and into bioenergy? Are we putting enough money into R&D? Should I spend more on lobbying? My son is studying for an MBA in the United States, but will there still be a profitable business for him to join when he graduates?

The orangutan carer A youngster in the forest.

Michael Catanzariti/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

A youngster in the forest.

Michael Catanzariti/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

We rescued Fi Fi from an area that used to be peatland forest but has been cleared for palm plantations. With no food and nowhere to make a nest, Fi Fi and her mother gradually got weaker and weaker, until workers at the plantation noticed and called us. The mother died before we could help her.

That was nine months ago, and I’ve been caring for Fi Fi around the clock since then in a babysitting team with my friend Nurmala. Fi Fi loves cuddles, milk and fruit, just like my children did at her age.

It is a good job, and we have a great team. Everyone is passionate about protecting the orangutans and the forest. We would like to be able to release Fi Fi once she has learned all her forest skills. Orangutans can look after themselves from about seven years old. But they need a lot of space.

Peatland fires, logging and oil palm planting destroy more forest every year, so places for Fi Fi to be released are hard to find. My brothers and sisters are all happy to stay living near our family home, and when I’m not here looking after Fi Fi, I always have my nieces and nephews on my knee.

I love to have them close, but when the dry season fires come and the haze is so thick I can’t even see my brother’s house across the street, I sometimes wish they had flown a bit further from the nest. Last year we were in and out of the health clinic for a month with my niece’s breathing problems.

I spend all my time caring for precious little ones – both human and orangutan – but the issues themselves are too big for me to fight.

Read more: Good news for the only place on Earth where tigers, rhinos, orangutans and elephants live together.

A way forward?People are central to the problem of tropical peatland fires. In their natural state, tropical peat swamp forests are too wet to burn. Drainage, installed by people for forestry, palm oil, roads, mining and other development, lowers the water table and dries out the peat. Many peat fires smoulder for months, from the start of dry season in July until the monsoon returns in November.

These fires have a wide range of negative effects: on local health, regional economies and the global carbon cycle. Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, has created a new Peatland Restoration Agency, and announced policies to restrict burning and draining of the peat beyond a maximum water table depth of 40cm below the surface. However, action is still disjointed and ministries are, at times, working at cross purposes.

The truth is that only when enough people value wet peatlands will the fires be prevented. Wet peatlands are great for orangutans and the global climate, but how about local smallholders, government officials and business investors? Saving peatlands will require creating value for these people too.

What crops can be profitably grown with a water table high enough to prevent burning? How can smallholders tap into a carbon trading market? Rather than cutting trees to send their children to school, can they earn more money by protecting the carbon stored in peat? Can villagers be empowered to make a better living from ecotourism than illegal logging?

Humans are integral to Indonesia’s tropical peatlands. And they must be at the centre of the solutions too. Otherwise the fires will keep burning – and none of the four people whose stories we’ve heard want that.

This article was co-authored by Laura Graham of the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation and Niken Sakuntaladewi, a researcher with the World Agroforestry Centre.

Samantha Grover receives funding from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

Robert Edis has received funding from, and currently works for, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research,

Linda Sukamta does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

New rules for retailers, but don’t sit there waiting for your electricity bill to go down

It sounds like good news. After summoning the heads of Australia’s major electricity retailers to Canberra, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull yesterday announced that the government will take “decisive action to reduce energy prices for Australian families and businesses”.

But look a little closer. Yes, the retailers have agreed to some small but important measures that will make it easier for customers to find the best electricity deal. But there is no guarantee energy prices will fall. And your electricity bill will only be lower if you, the customer, take action.

Retailers’ current advantageAt the moment, retailers typically encourage consumers to sign up by offering a discount on the bill for a fixed period – normally one or two years. After this period expires, customers usually face higher prices for their electricity.

Read more: Poor households are locked out of green energy, unless governments help

Some lucky customers will be put on an equivalent tariff and their electricity costs will not change much. Others will lose the discount – which can be as much as 30% of the bill. And some unlucky customers will be placed on the retailer’s “standing offer” – usually the most expensive plans in the market.

All the retailers have to do is to send you a letter informing you of the change. Lots of customers find those letters too confusing or time-consuming to read, and throw them in the bin. Those who do read and understand it don’t necessarily take action: almost half of Australian households have not changed their electricity retailer in more than five years.

How the new deal could help youUnder the deal that Turnbull has brokered with the retailers, every consumer on a lapsing deal will be sent more comprehensive and helpful information that will encourage them to switch. This will include details of cheaper available offers, and information from websites that compare prices across the various plans and retailers.

Second, as the Grattan Institute recommended in our March report, Price Shock, retailers will now have to be more explicit about what happens if you don’t sign up to a new offer. Specifically, that means detailing exactly how much it is going to cost you.

Third, retailers will have to report to the Australian Energy Regulator how many customers are on lapsed deals. This may seem like a lot of red tape for not a lot of impact. But a lack of information on how many customers are on what type of deal has been a major barrier to understanding what is happening in the electricity market. This increased transparency will encourage retailers to reduce the number of customers they have on lapsed contracts.

Read more: A simple rule change can save billions for power networks and their customers

The new deal includes other welcome measures, mainly designed to help poor households reduce their bills and make sure they do not face increased costs as a result of late payments. (To be fair to the retailers, they already do a lot for customers whom they consider to be “in hardship”.)

It’s still down to youThe deal will doubtless improve the retail electricity market. Retailers will take on more responsibility for helping their customers onto a better deal. And those customers who are most at risk from very high prices will get more protection.

But these are only incremental steps and do not ensure that customers will pay less for their electricity. While more simple information will be available, it will still be up to the consumer to act on it. The bottom line remains the same: if you want to pay less for electricity, you need to search for and sign up to a cheaper deal.

Customers should be under no illusions. Energy prices are still going to be high for as far as the eye can see.

Gas prices remain way above historic levels. Wholesale electricity prices are also high. Network costs – the price we pay for the poles and wires – have grown enormously over the past 20 years, and ultimately those costs find their way onto our bills. And the much-needed policy stability on greenhouse emission reductions that can put downward pressure on electricity costs remains elusive.

Under the new rules, consumers might be able to get a cheaper deal, but this doesn’t mean they will get a cheap deal.

It may be months before we know whether the new measures are enough to encourage consumers to go out and find a cheaper plan or retailer. The danger is that, in a year’s time, too many consumers will still be stuck on expensive electricity deals.

Even if huge numbers of consumers switch, there are still fundamental issues in Australia’s electricity market. Prices won’t come down across the board until these are resolved.

This is a welcome move by the government. But it only addresses a fraction of the problems in the electricity market. The big question for the prime minister is, what next?

David Blowers does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Southeast Europe swelters through another heatwave with a human fingerprint

Searching for respite from the heat in one of Rome's fountains. Max Roxxi/Reuters

Searching for respite from the heat in one of Rome's fountains. Max Roxxi/ReutersParts of Europe are having a devastatingly hot summer. Already we’ve seen heat records topple in western Europe in June, and now a heatwave nicknamed “Lucifer” is bringing stifling conditions to areas of southern and eastern Europe.

Several countries are grappling with the effects of this extreme heat, which include wildfires and water restrictions.

Temperatures have soared past 40℃ in parts of Italy, Greece and the Balkans, with the extreme heat spreading north into the Czech Republic and southern Poland.

Some areas are having their hottest temperatures since 2007 when severe heat also brought dangerous conditions to the southeast of the continent.

The heat is associated with a high pressure system over southeast Europe, while the jet stream guides weather systems over Britain and northern Europe. In 2007 this type of split weather pattern across Europe persisted for weeks, bringing heavy rains and flooding to England with scorching temperatures for Greece and the Balkans.

Europe is a very well-studied region for heatwaves. There are two main reasons for this: first, it has abundant weather observations and this allows us to evaluate our climate models and quantify the effects of climate change with a high degree of confidence. Second, many leading climate science groups are located in Europe and are funded primarily to improve understanding of climate change influences over the region.

The first study to link a specific extreme weather event to climate change examined the record hot European summer of 2003. Since then, multiple studies have assessed the role of human influences in European extreme weather. Broadly speaking, we expect hotter summers and more frequent and intense heatwaves in this part of the world.

We also know that climate change increased deaths in the 2003 heatwaves and that climate change-related deaths are projected to rise in the future.

Climate change’s role in this heatwaveTo understand the role of climate change in the latest European heatwave, I looked at changes in the hottest summer days over southeast Europe – a region that incorporates Italy, Greece and the Balkans.

I calculated the frequency of extremely hot summer days in a set of climate model simulations, under four different scenarios: a natural world without human influences, the world of today (with about 1℃ of global warming), a 1.5℃ global warming world, and a 2℃ warmer world. I chose the 1.5℃ and 2℃ benchmarks because they correspond to the targets described in the Paris Agreement.

As the heatwave is ongoing, we don’t yet know exactly how much hotter than average this event will turn out to be. To account for this uncertainty I used multiple thresholds based on historically very hot summer days. These thresholds correspond to an historical 1-in-10-year hottest day, a 1-in-20-year hottest day, and a new record for the region exceeding the observed 2007 value.

While we don’t know exactly where the 2017 event will end up, we do know that it will exceed the 1-in-10 year threshold and it may well breach the higher thresholds too.

A clear human fingerprintWhatever threshold I used, I found that climate change has greatly increased the likelihood of extremely hot summer days. The chance of extreme hot summer days, like this event, has increased by at least fourfold because of human-caused climate change.

Climate change is increasing the frequency of hot summer days in southeast Europe. Likelihoods of the hottest summer days exceeding the historical 1-in-10 year threshold, one-in-20 year threshold and the current record are shown for four scenarios: a natural world, the current world, a 1.5℃ world, and a 2℃ world. Best estimate likelihoods are shown with 90% confidence intervals in parentheses.

Author provided

Climate change is increasing the frequency of hot summer days in southeast Europe. Likelihoods of the hottest summer days exceeding the historical 1-in-10 year threshold, one-in-20 year threshold and the current record are shown for four scenarios: a natural world, the current world, a 1.5℃ world, and a 2℃ world. Best estimate likelihoods are shown with 90% confidence intervals in parentheses.

Author provided

My analysis shows that under natural conditions the kind of extreme heat we’re seeing over southeast Europe would be rare. In contrast, in the current world and possible future worlds at the Paris Agreement thresholds for global warming, heatwaves like this would not be particularly unusual at all.

There is also a benefit to limiting global warming to 1.5℃ rather than 2℃ as this reduces the relative frequency of these extreme heat events.

As this event comes to an end we know that Europe can expect more heatwaves like this one. We can, however, prevent such extreme heat from becoming the new normal by keeping global warming at or below the levels agreed upon in Paris.

You can find out more about the methods used here.

Andrew King receives funding from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science.

'Gene drives' could wipe out whole populations of pests in one fell swoop

Gene drives aim to deliberately spread bad genes when invasive species such as mice reproduce. Colin Robert Varndell/shutterstock.com

Gene drives aim to deliberately spread bad genes when invasive species such as mice reproduce. Colin Robert Varndell/shutterstock.comWhat if there was a humane, targeted way to wipe out alien pest species such as mice, rats and rabbits, by turning their own genes on themselves so they can no longer reproduce and their population collapses?

Gene drives – a technique that involves deliberately spreading a faulty gene throughout a population – promises to do exactly that.

Conservationists are understandably excited about the possibility of using gene drives to clear islands of invasive species and allow native species to flourish.

Read more: Gene drives may cause a revolution, but safeguards and public engagement are needed.

Hype surrounding the technique continues to build, despite serious biosecurity, regulatory and ethical questions surrounding this emerging technology.

Our study, published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggests that under certain circumstances, genome editing could work.

The penguins on Antipodes Island currently live alongside a 200,000-strong invasive mouse population.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Good and bad genes

The penguins on Antipodes Island currently live alongside a 200,000-strong invasive mouse population.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Good and bad genes

The simplest way to construct a gene drive aimed at suppressing a pest population is to identify a gene that is essential for the pest species’ reproduction or embryonic development. A new DNA sequence – the gene-drive “cassette” – is then inserted into that gene to disrupt its function, creating a faulty version (or “allele”) of that gene.

Typically, faulty alleles would not spread through populations, because the evolutionary fitness of individuals carrying them is reduced, meaning they will be less likely than non-faulty alleles to be passed on to the next generation. But the newly developed CRISPR gene-editing technology can cheat natural selection by creating gene-drive sequences that are much more likely to be passed on to the next generation.

Read more: Now we can edit life itself, we need to ask how we should use such technology.

Here’s how the trick works. The gene-drive cassette contains the genetic information to make two new products: an enzyme that cuts DNA, and a molecule called a guide RNA. These products act together as a tiny pair of molecular scissors that cuts the second (normal) copy of the target gene.

To fix the cut, the cell uses the gene drive sequence as a repair template. This results in a copy of the gene drive (and therefore the faulty gene) on both chromosomes.

This process is called “homing” and, when switched on in the egg- or sperm-producing cells of an animal, it should guarantee that almost all of their offspring inherit the gene-drive sequence.

As the gene-drive sequence spreads, mating between carriers becomes more likely, producing offspring that possess two faulty alleles and are therefore sterile or fail to develop past the embryonic stage.

Will it work?Initial attempts to develop suppression drives will likely focus on invasive species with rapid life cycles that allow gene drives to spread rapidly. House mice are an obvious candidate because they have lots of offspring, they have been studied in great detail by biologists, and have colonised vast areas of the world, including islands.

In our study we developed a mathematical model to predict whether gene drives can realistically be used to eradicate invasive mice from islands.

Our results show that this strategy can work. We predict that a single introduction of just 100 mice carrying a gene drive could eradicate a population of 50,000 mice within four to five years.

But it will only work if the process of genetic homing – which acts to overcome natural selection – functions as planned.

Evolution fights backJust as European rabbits in Australia have developed resistance to the viruses introduced to control them, evolution could thwart attempts to use gene drives for biocontrol.

Experiments with non-vertebrate species show that homing can fail in some circumstances. For example, the DNA break can be repaired by an alternative mechanism that stitches the broken DNA sequence back together without copying the gene-drive template. This also destroys the DNA sequence targeted by the guide RNA, producing a “resistance allele” that can never receive the gene drive.

A recent study in mosquitos estimated that resistance alleles were formed in at least 2% of homing attempts. Our simulation experiments for mice confirm this presents a serious problem.

After accounting for low failure rates during homing, the creation and spread of resistance alleles allowed the modelled populations to rebound after an initial decline in abundance. Imperfect homing therefore threatens the ability of gene drives to eradicate or even suppress pest populations.

One potential solution to this problem is to encode multiple guide RNAs within the gene-drive cassette, each targeting a different DNA sequence. This should reduce homing failure rates by allowing “multiple shots on goal”, and avoiding the creation of resistance alleles in more cases.

To wipe out a population of 200,000 mice living on an island, we calculate that the gene-drive sequences would need to contain at least three different guide RNA sequences, to avoid the mice ultimately getting the better of our attempts to eradicate them.

From hype to realityAre gene drives a hyperdrive to pest control, or just hype? Part of the answer will come from experiments with gene drives on laboratory mice (with appropriate containment). That will help to provide crucial data to inform the debate about their possible deployment.

We also need more sophisticated computer modelling to predict the impacts on non-target populations if introduced gene drives were to spread beyond the populations targeted for management. Using simulation, it will be possible to test the performance and safety of different gene-drive strategies, including strategies that involve multiple drives operating on multiple genes.

Thomas Prowse receives funding from the ARC and NHMRC

Joshua Ross receives funding from the ARC, NHMRC and D2D CRC.

Paul Thomas receives funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Phill Cassey has received funding from the ARC and the Invasive Animals CRC.

Australia doesn't 'get' the environmental challenges faced by Pacific Islanders

Environmental threats in the Pacific Islands can be cultural as well as physical. Christopher Johnson/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Environmental threats in the Pacific Islands can be cultural as well as physical. Christopher Johnson/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SAWhat actions are required to implement nature-based solutions to Oceania’s most pressing sustainability challenges? That’s the question addressed by the recently released Brisbane Declaration on ecosystem services and sustainability in Oceania.

Compiled following a forum earlier this year in Brisbane, featuring researchers, politicians and community leaders, the declaration suggests that Australia can help Pacific Island communities in a much wider range of ways than simply responding to disasters such as tropical cyclones.

Many of the insights offered at the forum were shocking, especially for Australians. Over the past few years, many articles, including several on The Conversation, have highlighted the losses of beaches, villages and whole islands in the region, including in the Solomons, Catarets, Takuu Atoll and Torres Strait, as sea level has risen. But the forum in Brisbane highlighted how little many Australians understand about the implications of these events.

Over the past decade, Australia has experienced a range of extreme weather events, including Tropical Cyclone Debbie, which hit Queensland in the very week that the forum was in progress. People who have been directly affected by these events can understand the deep emotional trauma that accompanies damage to life and property.

At the forum, people from several Pacific nations spoke personally about how the tragedy of sea-level rise is impacting life, culture and nature for Pacific Islanders.

One story, which has become the focus of the play Mama’s Bones, told of the deep emotional suffering that results when islanders are forced to move from the land that holds their ancestors’ remains.

The forum also featured a screening of the film There Once Was an Island, which documents people living on the remote Takuu Atoll as they attempt to deal with the impact of rising seas on their 600-strong island community. Released in 2011, it shows how Pacific Islanders are already struggling with the pressure to relocate, the perils of moving to new homes far away, and the potentially painful fragmentation of families and community that will result.

There Once Was an Island.Their culture is demonstrably under threat, yet many of the people featured in the film said they receive little government or international help in facing these upheavals. Australia’s foreign aid budgets have since shrunk even further.

As Stella Miria-Robinson, representing the Pacific Islands Council of Queensland, reminded participants at the forum, the losses faced by Pacific Islanders are at least partly due to the emissions-intensive lifestyles enjoyed by people in developed countries.

Australia’s roleWhat can Australians do to help? Obviously, encouraging informed debate about aid and immigration policies is an important first step. As public policy researchers Susan Nicholls and Leanne Glenny have noted, in relation to the 2003 Canberra bushfires, Australians understand so-called “hard hat” responses to crises (such as fixing the electricity, phones, water, roads and other infrastructure) much better than “soft hat” responses such as supporting the psychological recovery of those affected.

Similarly, participants in the Brisbane forum noted that Australian aid to Pacific nations is typically tied to hard-hat advice from consultants based in Australia. This means that soft-hat issues – like providing islanders with education and culturally appropriate psychological services – are under-supported.

The Brisbane Declaration calls on governments, aid agencies, academics and international development organisations to do better. Among a series of recommendations aimed at preserving Pacific Island communities and ecosystems, it calls for the agencies to “actively incorporate indigenous and local knowledge” in their plans.

At the heart of the recommendations is the need to establish mechanisms for ongoing conversations among Oceanic nations, to improve not only understanding of each others’ cultures but of people’s relationships with the environment. Key to these conversations is the development of a common language about the social and cultural, as well as economic, meaning of the natural environment to people, and the building of capacity among all nations to engage in productive dialogue (that is, both speaking and listening).

This capacity involves not only training in relevant skills, but also establishing relevant networks, collecting and sharing appropriate information, and acknowledging the importance of indigenous and local knowledge.

Apart from the recognition that Australians have some way to go to put themselves in the shoes of our Pacific neighbours, it is very clear that these neighbours, through the challenges they have already faced, have many valuable insights that can help Australia develop policies, governance arrangements and management approaches in our quest to meet the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

This article was co-written by Simone Maynard, Forum Coordinator and Ecosystem Services Thematic Group Lead, IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management.

Steven Cork is affiliated with Australia21.

Kate Auty does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Poor households are locked out of green energy, unless governments help

A report released this week by the Australian Council of Social Service has pointed out that many vulnerable households cannot access rooftop solar and efficient appliances, describing the issue as a serious problem.

It has provoked controversy. Some have interpreted the report as an attack on emerging energy solutions such as rooftop solar. Others see it as exposing a serious structural crisis for vulnerable households.

The underlying issue is the fundamental change in energy solutions. As I pointed out in my previous column, we are moving away from investment by governments and large businesses in big power stations and centralised supply, and towards a distributed, diversified and more complex energy system. As a result, there is a growing focus on “behind the meter” technologies that save, store or produce energy.

What this means is that anyone who does not have access to capital, or is uninformed, disempowered or passive risks being disadvantaged – unless governments act.

The reality is that energy-efficient appliances and buildings, rooftop solar, and increasingly energy storage, are cost-effective. They save households money through energy savings, improved health, and improved performance in comparison with buying grid electricity or gas. But if you can’t buy them, you can’t benefit.

In the past, financial institutions loaned money to governments or big businesses to build power stations and gas supply systems. Now we need mechanisms to give all households and businesses access to loans to fund the new energy system.

Households that cannot meet commercial borrowing criteria, or are disempowered – such as tenants, those under financial stress, or those who are disengaged for other reasons – need help.

Governments have plenty of options.

They can require landlords to upgrade buildings and fixed appliances, or make it attractive for them to do so. Or a bit of both.

They can help the supply chain that upgrades buildings and supplies appliances to do this better, and at lower cost.

They can facilitate the use of emerging technologies and apps to identify faulty and inefficient appliances, then fund their replacement. Repayments can potentially be made using the resulting savings.

They can ban the sale of inefficient appliances by making mandatory performance standards more stringent and widening their coverage.

They can help appliance manufacturers make their products more efficient, and ensure that everyone who buys them know how efficient they are.

To expand on the last suggestion, at present only major household white goods, televisions and computer monitors are required to carry energy labels. If you are buying a commercial fridge, pizza oven, cooker, or stereo system, you are flying blind.

The Finkel Review made it clear that the energy industry will not lead on this. It clearly recommends that energy efficiency is a job for governments, and that they need to accelerate action.

It’s time for governments to get serious about helping everyone to join the energy transition, not just the most affluent.

Alan Pears has worked for government, business, industry associations public interest groups and at universities on energy efficiency, climate response and sustainability issues since the late 1970s. He is now an honorary Senior Industry Fellow at RMIT University and a consultant, as well as an adviser to a range of industry associations and public interest groups. His investments in managed funds include firms that benefit from growth in clean energy. He has shares in Hepburn Wind.

Climate change to blame for Australia's July heat

Winter hasn’t felt too wintry yet in much of Australia. Most of us have have had more sunshine, higher temperatures, and less rainfall than is normal for the time of year. In fact, Australia just had its warmest average daytime maximum temperatures for July since records began in 1910.

This July saw the warmest average maximum temperatures on record across Australia.

Bureau of Meteorology

This July saw the warmest average maximum temperatures on record across Australia.

Bureau of Meteorology

The north and centre of the continent saw the biggest temperature anomalies as Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland experienced record warm daytime July temperatures. Only the southwestern tip of Western Australia and western Tasmania had slightly below-average daytime temperatures.

Southern Australia was again very dry as the frontal systems that usually bring rain remained further south than usual.

Read more: Winter heatwaves are nice … as extreme weather events go.

For most of us, warm and dry winter conditions are quite pleasant. But with drought starting to rear its head and a severe bushfire season on the cards, some cooler wetter weather would be helpful to farmers and fire services across the country.

What caused the unusual warmth?Often when we have warmer winter weather in Australia it is linked to El Niño conditions in the Pacific or a positive Indian Ocean Dipole. Both of these Pacific and Indian Ocean patterns tend to shift atmospheric pressure patterns in a way that brings more stable conditions and warmer, drier weather to Australia.

This year, however, neither El Niño nor the Indian Ocean Dipole is playing a role in the warm weather. The sea surface temperature patterns in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are close to average, so neither of these factors is driving Australia’s record warmth.

A clear human fingerprintAnother factor that might have influenced the July heat is human-caused climate change.

To assess the role of climate change in this event, I used climate model simulations and a standard event-attribution method. I first evaluated the climate models to gauge how well they capture the observed temperatures over Australia during July. I then computed the likelihood of unusually warm July average maximum temperatures across Australia in two groups of climate model simulations: one representing the world of today, and another representing a world without human influences on the climate.

I found a very clear signal that human-induced climate change has increased the likelihood of warm July temperatures such as the ones we’ve just experienced. My results suggest that climate change increased the chances of this record July warmth by at least a factor of 12.

July heat is on the riseI also wanted to know if this kind of unusual July warmth over Australia will become more common in future.

I looked at climate model projections for the next century, and examined the chances of these warm conditions occurring in periods when global warming is at 1.5℃ and 2℃ above pre-industrial levels (we have had roughly 1℃ of global warming above these levels so far).

The 1.5℃ and 2℃ global warming targets were decided in the Paris Agreement, brokered in December 2015. Given that we are aiming to limit global warming to these levels it is vital that we have a good idea of the climate we’re likely to be living in at these levels of warming.

I found that even if we manage to limit global warming to 1.5℃ we can expect to experience such July heat (which is record-breaking by today’s standards) in about 28% of winters. At 2℃ of global warming, the chances of warm July temperatures like 2017 are 43% for any given year.

More Julys like this are on the way as the globe heats up.

Andrew King, Author provided

More Julys like this are on the way as the globe heats up.

Andrew King, Author provided

Given the benefits of fewer and less intense heat extremes over Australia at lower levels of global warming, there is a clear incentive to try and limit climate change as much as possible. If we can reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and hold global warming to the Paris target levels, we should be able to avoid the kind of unusual warmth we have seen this July becoming the new normal.

Andrew King receives funding from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science.

Another attack on the Bureau, but top politicians have stopped listening to climate change denial

Has the Australian climate change debate changed? You could be forgiven for thinking the answer is no.

Just this week The Australian has run a series of articles attacking the Bureau of Meteorology’s weather observations. Meanwhile, the federal and Queensland governments continue to promote Adani’s planned coal mine, despite considerable environmental and economic obstacles. And Australia’s carbon dioxide emissions are rising again.

So far, so familiar. But something has changed.

Those at the top of Australian politics are no longer debating the existence of climate change and its causes. Instead, four years after the Coalition was first elected, the big political issues are rising power prices and the electricity market. What’s happening?

Read more: No, the Bureau of Meteorology is not fiddling its weather data.

A few years ago, rejection of climate science was part of the Australian political mainstream. In 2013, the then prime minister Tony Abbott repeated a common but flawed climate change denial argument:

Australia has had fires and floods since the beginning of time. We’ve had much bigger floods and fires than the ones we’ve recently experienced. You can hardly say they were the result of anthropic [sic] global warming.

Abbott’s statement dodges a key issue. While fires and floods have always occurred, climate change can still alter their frequency and severity. In 2013, government politicians and advisers, such as Dennis Jensen and Maurice Newman, weren’t shy about rejecting climate science either.

The atmosphere is different in 2017, and I’m not just talking about CO₂ levels. Tony Abbott is no longer prime minister, Dennis Jensen lost preselection and his seat, and Maurice Newman is no longer the prime minister’s business advisor.

Which Australian politician most vocally rejects climate science now? It isn’t the prime minister or members of the Coalition, but One Nation’s Malcolm Roberts. In Australia, open rejection of human-induced climate change has moved to the political fringe.

Roberts has declared climate change to be a “fraud” and a “scam”, and talked about climate records being “manipulated by NASA”. He is very much a conspiracy theorist on climate, as he is on other topics including banks, John F. Kennedy, and citizenship. His approach to evidence is frequently at odds with mainstream thought.

This conspiratorial approach to climate change is turning up elsewhere too. I was startled by the author list of the Institute of Public Affairs’ new climate change book. Tony Heller (better known in climate circles by the pseudonym Steven Goddard) doesn’t just believe climate change is a “fraud” and a “scam”, but has also promoted conspiracy theories about the Sandy Hook school massacre. This is a country mile from sober science and policy analysis.

So where is the Australian political mainstream? It’s not denying recent climate change and its causes, but instead is now debating the policy responses. This is exemplified by political arguments about the electricity market, power prices, and the Finkel Review.

Read more: What I learned from debating science with trolls

While this is progress, it’s not without serious problems. The debate may have rightly moved on to policy rather than science, but arguments for “clean coal” power are at odds with coal’s high CO₂ emissions and the failure thus far of carbon capture. Even power companies show little interest in new coal-fired power plants to replace those that have closed.

The closure of the Hazelwood power station was politically controversial.

Jeremy Buckingham/flickr

History repeating?

The closure of the Hazelwood power station was politically controversial.

Jeremy Buckingham/flickr

History repeating?

Have those who rejected global warming and its causes changed their tune? In general, no. They still imagine that scientists are up to no good. The Australian’s latest attacks on the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) illustrate this, especially as they are markedly similar to accusations made in the same newspaper three years ago.

This week, the newspaper’s environment editor Graham Lloyd wrote that the BoM was “caught tampering” with temperature logs, on the basis of measurements of cold temperatures on two July nights at Goulburn and Thredbo. For these nights, discrepant temperatures were in public BoM databases due to automated weather stations that stopped reporting data. The data points were flagged for BoM staff to verify, but in the meantime an amateur meteorologist contacted Lloyd and the Institute of Public Affairs’ Jennifer Marohasy.

In 2014, Lloyd cast doubt on the BoM’s climate record by attacking the process of “homogenisation,” with a particular emphasis on data from weather stations in Rutherglen, Amberley and Bourke. Homogenisation is used to produce a continuous temperature record from measurements that may suffer from artificial discontinuities, such as in the case of weather stations that have been upgraded or moved from, say, a post office to an airport.

The Tuggeranong Automatic Weather Station.

Bidgee/Wikimedia Commons

The Tuggeranong Automatic Weather Station.

Bidgee/Wikimedia Commons

Lloyd’s articles from this week and 2014 are beat-ups, for similar reasons. The BoM’s ACORN-SAT long-term temperature record is compiled using daily measurements from 112 weather stations. Even Lloyd acknowledges that those 112 stations don’t include Goulburn and Thredbo. While Rutherglen, Amberley and Bourke do contribute to ACORN-SAT, homogenisation of their data (and that of other weather stations) does little to change the warming trend measured across Australia. Australia has warmed over the past century, and The Australian’s campaigns won’t change that.

In 2014, the government responded to The Australian’s campaign by commissioning the Technical Advisory Forum, which has since reviewed ACORN-SAT and found it to be a “well-maintained dataset”. Prime Minister Abbott also considered a taskforce to investigate BoM, but was dissuaded by the then environment minister Greg Hunt.

How will Malcolm Turnbull’s government respond to The Australian’s retread of basically the same campaign? Perhaps that will be the acid test for whether the climate debate really has changed.

Michael J. I. Brown receives research funding from the Australian Research Council and Monash University, and has developed space-related titles for Monash University's MWorld educational app.