The Conversation

How farming giant seaweed can feed fish and fix the climate

Giant kelp can grow up to 60cm a day, given the right conditions. Joe Belanger/shutterstock.com

Giant kelp can grow up to 60cm a day, given the right conditions. Joe Belanger/shutterstock.comThis is an edited extract from Sunlight and Seaweed: An Argument for How to Feed, Power and Clean Up the World by Tim Flannery, published by Text Publishing.

Bren Smith, an ex-industrial trawler man, operates a farm in Long Island Sound, near New Haven, Connecticut. Fish are not the focus of his new enterprise, but rather kelp and high-value shellfish. The seaweed and mussels grow on floating ropes, from which hang baskets filled with scallops and oysters. The technology allows for the production of about 40 tonnes of kelp and a million bivalves per hectare per year.

The kelp draw in so much carbon dioxide that they help de-acidify the water, providing an ideal environment for shell growth. The CO₂ is taken out of the water in much the same way that a land plant takes CO₂ out of the air. But because CO₂ has an acidifying effect on seawater, as the kelp absorb the CO₂ the water becomes less acid. And the kelp itself has some value as a feedstock in agriculture and various industrial purposes.

After starting his farm in 2011, Smith lost 90% of his crop twice – when the region was hit by hurricanes Irene and Sandy – but he persisted, and now runs a profitable business.

His team at 3D Ocean Farming believe so strongly in the environmental and economic benefits of their model that, in order to help others establish similar operations, they have established a not-for-profit called Green Wave. Green Wave’s vision is to create clusters of kelp-and-shellfish farms utilising the entire water column, which are strategically located near seafood transporting or consumption hubs.

Read more: Seaweed could hold the key to cutting methane emissions from cow burps

The general concepts embodied by 3D Ocean Farming have long been practised in China, where over 500 square kilometres of seaweed farms exist in the Yellow Sea. The seaweed farms buffer the ocean’s growing acidity and provide ideal conditions for the cultivation of a variety of shellfish. Despite the huge expansion in aquaculture, and the experiences gained in the United States and China of integrating kelp into sustainable marine farms, this farming methodology is still at an early stage of development.

Yet it seems inevitable that a new generation of ocean farming will build on the experiences gained in these enterprises to develop a method of aquaculture with the potential not only to feed humanity, but to play a large role in solving one of our most dire issues – climate change.

Globally, around 12 million tonnes of seaweed is grown and harvested annually, about three-quarters of which comes from China. The current market value of the global crop is between US$5 billion and US$5.6 billion, of which US$5 billion comes from sale for human consumption. Production, however, is expanding very rapidly.

Seaweeds can grow very fast – at rates more than 30 times those of land-based plants. Because they de-acidify seawater, making it easier for anything with a shell to grow, they are also the key to shellfish production. And by drawing CO₂ out of the ocean waters (thereby allowing the oceans to absorb more CO₂ from the atmosphere) they help fight climate change.

The stupendous potential of seaweed farming as a tool to combat climate change was outlined in 2012 by the University of the South Pacific’s Dr Antoine De Ramon N’Yeurt and his team. Their analysis reveals that if 9% of the ocean were to be covered in seaweed farms, the farmed seaweed could produce 12 gigatonnes per year of biodigested methane which could be burned as a substitute for natural gas. The seaweed growth involved would capture 19 gigatonnes of CO₂. A further 34 gigatonnes per year of CO₂ could be taken from the atmosphere if the methane is burned to generate electricity and the CO₂ generated captured and stored. This, they say:

…could produce sufficient biomethane to replace all of today’s needs in fossil-fuel energy, while removing 53 billion tonnes of CO₂ per year from the atmosphere… This amount of biomass could also increase sustainable fish production to potentially provide 200 kilograms per year, per person, for 10 billion people. Additional benefits are reduction in ocean acidification and increased ocean primary productivity and biodiversity.

Nine per cent of the world’s oceans is not a small area. It is equivalent to about four and a half times the area of Australia. But even at smaller scales, kelp farming has the potential to substantially lower atmospheric CO₂, and this realisation has had an energising impact on the research and commercial development of sustainable aquaculture. But kelp farming is not solely about reducing CO₂. In fact, it is being driven, from a commercial perspective, by sustainable production of high-quality protein.

A haven for fish.

Daniel Poloha/shutterstock.com

A haven for fish.

Daniel Poloha/shutterstock.com

What might a kelp farming facility of the future look like? Dr Brian von Hertzen of the Climate Foundation has outlined one vision: a frame structure, most likely composed of a carbon polymer, up to a square kilometre in extent and sunk far enough below the surface (about 25 metres) to avoid being a shipping hazard. Planted with kelp, the frame would be interspersed with containers for shellfish and other kinds of fish as well. There would be no netting, but a kind of free-range aquaculture based on providing habitat to keep fish on location. Robotic removal of encrusting organisms would probably also be part of the facility. The marine permaculture would be designed to clip the bottom of the waves during heavy seas. Below it, a pipe reaching down to 200–500 metres would bring cool, nutrient-rich water to the frame, where it would be reticulated over the growing kelp.

Von Herzen’s objective is to create what he calls “permaculture arrays” – marine permaculture at a scale that will have an impact on the climate by growing kelp and bringing cooler ocean water to the surface. His vision also entails providing habitat for fish, generating food, feedstocks for animals, fertiliser and biofuels. He also hopes to help exploited fish populations rebound and to create jobs. “Given the transformative effect that marine permaculture can have on the ocean, there is much reason for hope that permaculture arrays can play a major part in globally balancing carbon,” he says.

The addition of a floating platform supporting solar panels, facilities such as accommodation (if the farms are not fully automated), refrigeration and processing equipment tethered to the floating framework would enhance the efficiency and viability of the permaculture arrays, as well as a dock for ships carrying produce to market.

Given its phenomenal growth rate, the kelp could be cut on a 90-day rotation basis. It’s possible that the only processing required would be the cutting of the kelp from the buoyancy devices and the disposal of the fronds overboard to sink. Once in the ocean depths, the carbon the kelp contains is essentially out of circulation and cannot return to the atmosphere.

The deep waters of the central Pacific are exceptionally still. A friend who explores mid-ocean ridges in a submersible once told me about filleting a fish for dinner, then discovering the filleted remains the next morning, four kilometres down and directly below his ship. So it’s likely that the seaweed fronds would sink, at least initially, though gases from decomposition may later cause some to rise if they are not consumed quickly. Alternatively, the seaweed could be converted to biochar to produce energy and the char pelletised and discarded overboard. Char, having a mineralised carbon structure, is likely to last well on the seafloor. Likewise, shells and any encrusting organisms could be sunk as a carbon store.

Once at the bottom of the sea three or more kilometres below, it’s likely that raw kelp, and possibly even to some extent biochar, would be utilised as a food source by bottom-dwelling bacteria and larger organisms such as sea cucumbers. Provided that the decomposing material did not float, this would not matter, because once sunk below about one kilometre from the surface, the carbon in these materials would effectively be removed from the atmosphere for at least 1,000 years. If present in large volumes, however, decomposing matter may reduce oxygen levels in the surrounding seawater.

Large volumes of kelp already reach the ocean floor. Storms in the North Atlantic may deliver enormous volumes of kelp – by some estimates as much as 7 gigatonnes at a time – to the 1.8km-deep ocean floor off the Bahamian Shelf.

Submarine canyons may also convey large volumes at a more regular rate to the deep ocean floor. The Carmel Canyon, off California, for example, exports large volumes of giant kelp to the ocean depths, and 660 major submarine canyons have been documented worldwide, suggesting that canyons play a significant role in marine carbon transport.

These natural instances of large-scale sequestration of kelp in the deep ocean offer splendid opportunities to investigate the fate of kelp, and the carbon it contains, in the ocean. They should prepare us well in anticipating any negative or indeed positive impacts on the ocean deep of offshore kelp farming.

Only entrepreneurs with vision and deep pockets could make such mid-ocean kelp farming a reality. But of course where there are great rewards, there are also considerable risks. One obstacle potential entrepreneurs need not fear, however, is bureaucratic red tape, for much of the mid-oceans remain a global commons. If a global carbon price is ever introduced, the exercise of disposing of the carbon captured by the kelp would transform that part of the business from a small cost to a profit generator. Even without a carbon price, the opportunity to supply huge volumes of high-quality seafood at the same time as making a substantial impact on the climate crisis are considerable incentives for investment in seaweed farming.

Tim Flannery does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Pig-hunting dogs and humans are at risk of a disease that can cause miscarriages and infertility

Feral pigs are found in every state and territory in Australia. Shutterstock

Feral pigs are found in every state and territory in Australia. ShutterstockA disease called swine brucellosis is emerging in New South Wales, carried by feral pigs. Endemic to feral pigs in Queensland, and sometimes infecting the dogs used to hunt them, it can be transmitted to humans through blood contact with infected pigs. A number of people have already been infected in NSW.

Recreational pig hunting in rural Australia is a widespread control method for the roughly 24 million feral pigs who call Australia home.

The ethics of this undertaking is open to debate – many authorities consider poisoning more efficient and more ethical than hunting. But regardless of this controversy, the emergence of swine brucellosis illustrates the risk that comes with hunting.

Read more: How dog saliva spreads potentially deadly bacteria to people

How swine brucellosis spreadsHunting and killing feral pigs is risky to all participants. Adult pigs are large, powerful animals, and their tusks can inflict serious injuries to both human and canine combatants. Despite the leather armour given to pig-hunting dogs, they commonly receive penetrating injuries. These can cause substantial wounds, peritonitis (inflammation of the lining of the abdominal cavity) and even death.

Despite the armour worn by pig-hunting dogs, they are at risk of cuts and infection from pigs.

Babes & Boars/Facebook

Despite the armour worn by pig-hunting dogs, they are at risk of cuts and infection from pigs.

Babes & Boars/Facebook

These risks are of course well understood by the people that hunt pigs. But regrettably, many tend to their dogs’ injuries without veterinary assistance. Most feral pigs show little outward signs of the disease, so the danger to man and dog can be hidden even to an experienced “pigger”.

People and dogs can be infected if they have a break in their skin (such as a minor wound or abrasion) that becomes contaminated with the blood or tissue of a pig or dog carrying the pathogen. This can occur during capture, or when the pig carcass is “dressed” in the field. Veterinarians in Australia have also been infected with Brucella suis following surgery on infected dogs.

In people, brucellosis is a systemic disease which can result in undulant fever, lassitude, sore joints and back pain. More serious cases involve orchitis and epididymitis (swollen testicles), miscarriage as well as kidney, liver or cardiovascular disease. As TIME magazine famously reported in 1943, “the disease rarely kills anybody but it often makes a patient wish he were dead.”

Feral pigs are found in every state and territory in Australia, but their highest concentration is in Queensland.

National Land and Water Resources Audit

Feral pigs are found in every state and territory in Australia, but their highest concentration is in Queensland.

National Land and Water Resources Audit

Brucellosis (caused by bacterium Brucella suis) can usually be rapidly diagnosed through blood tests and other clinical investigations, as long as the history of pig hunting is disclosed to the medical team. Although there is usually a connection to pig hunting, humans can also be infected by accidental contact with the organism in diagnostic laboratories.

Swine brucellosis is seen only in feral pigs in Australia, and there is currently no risk to humans from pigs kept in modern intensive piggeries. The disease is considered endemic in Queensland, but it appears to be emerging in NSW. We see it more and more commonly in canine patients in the northern parts of the state, as the disease extends its biological range.

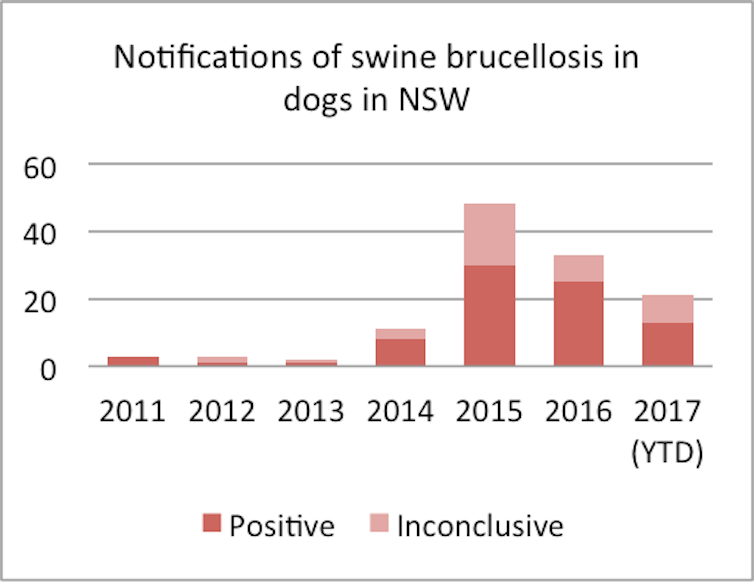

There’s been a dramatic increase in swine brucellosis cases in NSW.

Data from the Department of Primary Industries

There’s been a dramatic increase in swine brucellosis cases in NSW.

Data from the Department of Primary Industries

This might be a natural process, although some people suspect the deliberate (and illegal) capture and relocation of young feral pigs from Queensland to NSW plays a key role in the spread of infection.

Location of swine brucellosis cases in dogs.

Data from the Department of Primary Industries

How to protect yourself and your animals

Location of swine brucellosis cases in dogs.

Data from the Department of Primary Industries

How to protect yourself and your animals

There are some simple recommendations which will reduce the risk of infections in people who hunt pigs, and their families:

when handling pig carcasses, always cover any skin cuts with waterproof dressings, and if possible, use disposable gloves

minimise exposure to blood, fluids and organs and always wash hands and arms with soap and water afterwards

mesh protective gloves should be worn when dressing pigs in the field

Our focus has been the disease that occurs in “pig dogs”, who are at risk of infection from hunting injuries and the practice of feeding raw feral pig meat or offal to dogs after they are dressed in the field. Non-hunting “house dogs” of pig hunters can also be infected if they are fed feral pig flesh.

Pig dogs often live alongside ‘house dogs’, who can also be at risk of infection.

Facebook

Pig dogs often live alongside ‘house dogs’, who can also be at risk of infection.

Facebook

This can make the diagnosis harder, as the relationship with pig hunting is not apparent. To make matters even more complex the disease can have a long incubation period, so dogs from the country can be infected while young, make their way into pounds and be rescued by people from urban areas where pig hunting is alien, and not often considered by city veterinarians. In one case, a female dog in Sydney had two years of extensive investigation into her lameness and back pain before diagnosis.

Dogs with swine brucellosis can develop various signs including swollen testicles, back pain, joint involvement, abortion as well as the less specific signs of fever and lassitude. The NSW Department of Primary Industries currently provides free testing through the Elizabeth Macarthur Agriculture Institute in New South Wales.

It’s not all bad news. While euthanasia may be recommended to protect public health, preliminary evidence suggests the disease can be treated in dogs using combination therapy with two antibiotics (rifampicin and doxycycline) which are relatively inexpensive. Ideally, this is combined with castration or removal of the ovaries and uterus, to remove any residual infected gonadal tissue. It’s too early to tell whether dogs are cured for good but the results are looking promising.

Read more: Protect your puppies: vaccinate them against a new strain of parvo

Prevention is always better than cure, so one obvious solution would be to use poisoning of feral pigs as a method of population control rather than hunting. If hunting cannot be prevented, it is strongly recommended that feral pig meat is thoroughly cooked before feeding it to dogs or people – this also kills the parasite that cause sparganosis and the bacteria which cause Q fever. Do not let pig-hunting dogs lick humans, and always wash your hands after contact with feral pigs or dogs.

More information about brucellosis and feral pig hunting and brucellosis in dogs can be found on government websites.

Siobhan Mor has received funding from the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Hunter New England Population Health in support of her research on canine brucellosis.

Richard Malik does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Australian recycling plants have no incentive to improve

In the wake of a devastating fire at the Melbourne Coolaroo recycling facility earlier this month, Victorian environment minister Lily D'Ambrosio has announced a statewide audit of recycling facilities.

The audit is designed to identify other facilities with dangerous stockpiles of paper and plastic, but will also have the benefit of simply telling us how many plants are in Victoria.

It’s currently almost impossible to say how many recycling facilities are in Australia, where they are, and what they’re capable of sorting. And market forces can incentivise stockpiling material, creating the potential for yet more severe fires.

Where does our recycling go?Australia generates roughly 50 million tonnes of waste a year, around 50-60% of which is recycled.

Some is defined as “construction and demolition” waste and recycled at specialist facilities, while a portion of food and garden waste is composted.

Most of the rest is collected from businesses and households, sorted at a recycling facility and then sent on to another facility to be turned into new products or packaging.

Overall, the volume of waste we generate generating is increasing at an estimated 7-10% per annum – more waste and recyclables that require sorting.

According to a 2013 report from the Department of Environment and Energy there are an estimated 114 facilities in Australia that sort recyclables from the commercial/industrial and household sectors.

However, this tells us very little. We don’t know the true number, as each council licenses the facilities in their area but there’s no central database. Some will manage household recyclables, while some will specialise in materials like paper and cardboard, or glass.

These facilities vary in how much volume they can process, as well as the variety of materials. Some rely totally on human labour to sort the materials, and others are a mix of mechanical and labour.

In light of our growing need for recycling facilities (and events like the Coolaroo fire), it’s clear that we need a national registry, updated with an annual survey.

Private companies recycle for AustraliaAcross Australia, most recycling is done by private companies. Councils are responsible for collecting household recyclables, but with very few exceptions they pay businesses to do it. Regardless, we are charged for the service through our rates.

Many different materials can be recycled – even plastic shopping bags and polystyrene. But it requires dedicated equipment at the recycling facilities to do so, and well as a market for the sorted product. Installing plastic-bag-recycling equipment is expensive and the markets are volatile, meaning that the expense for collection and sorting may not be repaid.

When prices for material like metal, glass or paper drop, companies may hold on to material waiting for an increase, or simply send them to landfill to reduce costs.

Another issue not often considered is the location of these facilities. As forward planning has been limited, new facilities will need to be placed in rural or regional areas, increasing transport costs and further shrinking the profit margins of the industry.

It also means more emissions as waste is transported from collection, to the sorting facility and then back to industry and shipping locations. At the same time, recyclables from many regional councils are transported to specialist sorting facilities located closer to metropolitan Melbourne, as there are no such facilities close to them.

What we can do to fix itFundamentally, Australians want more recycling, less landfill and less overall waste. Fortunately there are a number of process that can help deliver these outcomes.

States and territories can upgrade recycling facilities. New South Wales has been extremely proactive in spending money from its landfill levy to improve waste management, but the Victorian government has a A$500 million sustainability fund that should be used for the same purpose.

Particular attention should be paid to increasing our capacity to sort more materials, diverting them from landfill.

Tax breaks and other financial incentives should be offered to plant operators who upgrade their equipment, and manufacturers who use recyclable material in their products.

At the same time, we should consider penalising businesses who use non-recyclable packaging when alternatives exist, and retailers who sell goods in multi-material packaging (like polystyrene and plastic) without providing an alternative.

It should be possible to buy fruit or vegetables not wrapped in multiple kinds of packaging.

ricardo/Flickr, CC BY

It should be possible to buy fruit or vegetables not wrapped in multiple kinds of packaging.

ricardo/Flickr, CC BY

Recycling is very different to landfills, which are also generally privately owned. There’s significant government investment in landfill, as well as strict environmental and social restrictions. Importantly, landfills are not subject to the same market forces that cause large price fluctuations.

While the Victorian audit is a positive step, it does not address the basic lack of sorting facilities in the right locations, without policies to encourage development.

Recycling reduces overall greenhouse gas emissions, and energy, water and raw material consumption. Yet, apart from continual policy statements, little is being done.

Of course, it’s a complex issue. Forcing recyclers to sell their product at low rates can cause businesses to collapse; at the same time, less valuable material can end up in clearly dangerous stockpiles or yet more landfill.

Kneejerk reactions are not the answer. First and foremost, we need to find out how many facilities exist across Australia, where they are and what their capacity is. Only then can we usefully plan.

Trevor Thornton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Finally facing our water-loo: it's time to decolonise sewerage systems

Colonial notions of public and private space are embedded in sewage systems. Elaichi Ohyeah/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Colonial notions of public and private space are embedded in sewage systems. Elaichi Ohyeah/Flickr, CC BY-SATwo current global trends are set to make life rather uncomfortable for cities: climate change and the unprecedented rate of urbanisation.

This combination of extreme weather – often involving sudden deluges of water – and high population density will test even the best sewage infrastructure we have today. In the face of such pressures, how adaptable are our sewage systems?

Colonial heritage in our sewage systemsSewage systems worldwide commonly consist of flush toilets and pipes that rely on a steady supply of water to transport and deposit bodily waste, either to a wastewater treatment plant or, failing that, simply downstream in the nearest river or straight into the ocean.

Many urbanites around the globe are using sewage systems based on a colonial-era template. Initially implemented to cure London’s “Great Stink” of 1858, when a hot summer combined with the excrement-filled River Thames to create an unbearable stench, sewer systems were public health interventions designed to remove pathogens and “miasmatic” offences associated with bodily waste.

They were first transplanted off Britain’s shores in the reconstruction of Paris from 1850–70, and since then have become embedded culture-specific notions of hygiene and sanitation around the globe.

Such colonial infrastructure is now proving increasingly problematic in the face of human-driven global trends (broadly referred to as the Anthropocene).

Using water to flush wasteA paradox of climate change is that there seems to be both more and less water. In South Asia, for example, at least 1.6 billion people struggle to find drinking water despite an abundance of water generally.

A woman siphoning water from a leaky pipe into a bucket on the side of the road during summer.

Author provided

A woman siphoning water from a leaky pipe into a bucket on the side of the road during summer.

Author provided

For residents of Darjeeling, India, where I am currently conducting my PhD fieldwork, this paradox is very real. Monsoons in Darjeeling last from June through August, sometimes longer, and rain falls frequently throughout the rest of the year. On the face of it, Darjeeling should have plenty of water, but in fact it faces increasingly acute shortages during the summer months from April to June.

The town’s water and waste infrastructure was built by the British in the 1930s, for what was then a population of 10,000. Its population now hovers around the 150,000 mark, and surges to more than 200,000 during peak tourist season from March to May. Despite this, there has been little to no official maintenance or upgrade since Indian independence in 1947.

In town, signs that urbanisation has outpaced infrastructure capacity are everywhere. An impressive number of pipes move water to and from the population. Along with electricity wires, these pipes traverse the city along increasingly bizarre and precarious routes. Ad hoc retrofit attempts to meet rising demand appear to be band-aid solutions and, because the pipes leak, often exacerbate contamination.

A typical open sewer in Darjeeling. Note the pipes on either side are water pipes taking drinking water to homes.

Author provided

A typical open sewer in Darjeeling. Note the pipes on either side are water pipes taking drinking water to homes.

Author provided

Darjeeling is instructive because it is a landscape struggling with inadequate infrastructure amid a rapidly urbanising population. In such a landscape, fresh water can be contaminated by sewage outflows, largely because the system is completely dependent on water to function.

Such over-reliance underpins another paradox: modern sewerage systems require water to work and yet, if not context-sensitive nor managed appropriately, can dirty vital waterways.

Closer to homeAustralia is not immune to such problems. Our changing climate means we too face more severe droughts along with heavier rainfall events. Under these conditions, our sewage systems are under increasing stress.

Earlier this year Melbourne experienced summer flash floods which strained the city’s sewage systems, contaminating three public beaches. In February a heavy downpour in Western Australia caused concern over sewage contamination in the Swan River.

Such experiences are not isolated, and are likely to increase in incidence across the world. They provide important lessons and act as a catalyst for rethinking our relationship to water and waste, particularly amid concerns over water scarcity and extreme weather conditions in southern Australia.

Alternative futuresMany social scientists are now researching alternative forms of infrastructure that are contextually relevant, embedded in community values, and adaptable to current environmental challenges.

These alternative forms include moves to re-examine our relationship with waste in farming, use dry composting toilets, and install public bio-toilets along India’s main railway corridors.

As for my home town of Adelaide, the capital of the driest state on the driest inhabited continent on Earth, should we really continue to use water to flush bodily waste?

Matt Barlow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Supreme Court ruling on NZ's largest irrigation dam proposal respects conservation law and protected land

This aerial view shows the catchment of the Makaroro river, in the Ruahine Forest Park. The river was to be dammed for the Ruataniwha irrigation scheme. Peter Scott, CC BY-ND

This aerial view shows the catchment of the Makaroro river, in the Ruahine Forest Park. The river was to be dammed for the Ruataniwha irrigation scheme. Peter Scott, CC BY-NDEarlier this month, New Zealand’s Supreme Court rejected a proposed land swap that would have flooded conservation land for the construction of the country’s largest irrigation dam.

The court was considering whether the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council’s investment arm could build a dam on 22 hectares of the protected Ruahine Forest Park in exchange for 170 hectares of private farm land. The proposed dam is part of the $900 million Ruataniwha water storage and irrigation scheme.

The New Zealand government’s response to the ruling was to consider a law change to make land swaps easier. Such a move flies in the face of good governance.

Natural capital vs developmentThe Supreme Court ruling has significant implications for the Ruataniwha dam. In addition, it asserts the importance of permanent protection of high-value conservation land.

The ecological value of the Ruahine Forest Park land was never in question. The conservation land includes indigenous forest, a unique braided river and wetlands that would have been destroyed.

The area is home to a dozen plants and animals that are classified as threatened or at risk. The developer’s ecological assessment acknowledged the destruction of ecologically significant land and water bodies. However, it argued that mitigation and offsetting would ensure that any effects of habitat loss were at an acceptable level.

The Mohaka River also flows through the Hawke’s Bay.

Christine Cheyne, CC BY-ND

Challenge to NZ’s 100% Pure brand

The Mohaka River also flows through the Hawke’s Bay.

Christine Cheyne, CC BY-ND

Challenge to NZ’s 100% Pure brand

New Zealand’s environmental legislation states that adverse effects are to be avoided, remedied or mitigated. However, no priority is given to avoiding adverse effects. Government guidance on offsetting does not require outcomes with no net loss.

In Pathways to prosperity, policy analyst Marie Brown argues that offsetting is not always appropriate when the affected biodiversity is vulnerable and irreplaceable.

Recent public concern about declining water quality has provided significant momentum to address pollution and over-allocation to irrigation. Similarly, awareness of New Zealand’s loss of indigenous biodiversity is building.

These issues were highlighted in this year’s OECD Environmental Performance Review and a report by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment on the parlous state of New Zealand’s native birds.

Both issues damage New Zealand’s 100% Pure branding and pose significant risks to tourism and the export food sector. Indigenous ecosystems are a huge draw card to surging numbers of international tourists.

Battle lines in fight for the environmentPowerful economic arguments have been put forward by business actors, both internationally and in New Zealand. For example, Pure Advantage supports protection of ecosystems and landscapes. Yet, governance mechanisms are limited.

Since 2009, environmental protection and conservation have increasingly become major battle lines as the National government doggedly pursues its business growth agenda. This favours short-term economic growth over environmental protection.

A key principle behind the Supreme Court decision is that protected conservation land cannot be traded off. It follows a High Court case in which environmental organisations argued unsuccessfully that the transfer of land was unlawful.

However, in August 2016, the Court of Appeal ruled against the Director-General of Conservation’s decision to allow the land transfer. It had been supported on the grounds that there would be a net gain to the conservation estate. The court’s ruling said that the intrinsic values of the protected land had been disregarded.

The Supreme Court has reinforced the importance of the permanent protection status recognised by the Court of Appeal.

Anticipatory governanceIn response to the court’s decisions, the government argued that land swaps of protected areas should be allowed. It may seek to amend legislation to facilitate such exchanges.

The Supreme Court made reference to section 2 of the Conservation Act 1987. It defines conservation as “the preservation and protection of natural and historic resources for the purpose of maintaining their intrinsic values, providing for their appreciation and recreational enjoyment by the public, and safeguarding the options of future generations”.

Section 6 of the act states that the Department of Conservation should “promote the benefits to present and future generations of the conservation of natural and historic resources”. As such, the legislation and the department contribute to what is known as “anticipatory governance”.

Anticipatory governance is fundamental to good governance, as Jonathan Boston argues in his recent publication Safeguarding the future: governing in an uncertain world.

It requires protecting long-term public interests. Conservation of our unique ecosystems and landscapes protects their intrinsic values and the services they provide. These include tourism benefits and basic needs such as water, soil and the materials that sustain human life.

The department has correctly recognised that conservation promotes prosperity. However, long-term prosperity is quite different from the short-term exploitation associated with the government’s business growth agenda.

This promotes exploitation in the form of mining on conservation land and increased infrastructure for tourism and other industries, such as the proposed Ruataniwha dam.

Amending the Conservation Act to allow land swaps involves a significant discounting of the future in favour of present day citizens. This is disingenuous and an affront to constitutional democracy. It would weaken one of New Zealand’s few anticipatory governance mechanisms at a time when they are needed more than ever.

Christine Cheyne was a member of the Taranaki-Whanganui Conservation Board for 10 years (2004-2014).

Is the Murray-Darling Basin Plan broken?

A recent expose by the ABC’s Four Corners has alleged significant illegal extraction of water from the Barwon-Darling river system, one of the major tributaries of the Murray River. The revelations have triggered widespread condemnation of irrigators, the New South Wales government and its officials, the Murray-Darling Basin Authority and the Basin Plan itself.

If the allegations are true that billions of litres of water worth millions of dollars were illegally extracted, this would represent one of the largest thefts in Australian history. It would have social and economic consequences for communities along the entire length of the Murray-Darling river system, and for the river itself, after years of trying to restore its health.

Water is big business, big politics and a big player in our environment. Taxpayers have spent A$13 billion on water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin in the past decade, hundreds of millions of which have gone directly to state governments. Governments have an obligation to ensure that this money is well spent.

The revelations cast doubt on the states’ willingness to do this, and even on their commitment to the entire Murray-Darling Basin Plan. This commitment needs to be reaffirmed urgently.

Basic principlesTo work out where to go from here, it helps to understand the principles on which the Basin Plan was conceived. At its foundation, Australian water reform is based on four pillars.

1. Environmental water and fair consumption

The initial driver of water reform in the late 1990s was a widespread recognition that too much water had been allocated from the Murray-Darling system, and that it had suffered ecological damage as a result.

State and Commonwealth governments made a bipartisan commitment to reset the balance between water consumption and environmental water, to help restore the basin’s health and also to ensure that water-dependent industries and communities can be strong and sustainable.

Key to this was the idea that water users along the river would have fair access to water. Upstream users could not take water to the detriment of people downstream. The Four Corners investigation casts doubt on the NSW’s commitment to this principle.

2. Water markets and buybacks

The creation of a water market under the Basin Plan had two purposes: to allow water to be purchased on behalf of the environment, and to allow water permits to be traded between irrigators depending on relative need.

This involved calculating how much water could be taken from the river while ensuring a healthy ecosystem (the Sustainable Diversion Limit). Based on these calculations, state governments developed a water recovery program, which aimed to recover 2,750 gigalitres of water per year from consumptive use, through a A$3 billion water entitlement buyback and a A$9 billion irrigation modernisation program.

This program hinged on the development of water accounting tools that could measure both water availability and consumption. Only through trust in this process can downstream users be confident that they are receiving their fair share.

3. States retain control of water

Control of water was a major stumbling block in negotiating the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, because of a clash between states’ water-management responsibilities and the Commonwealth’s obligations to the environment.

As a result, the Murray-Darling Basin Authority sits outside of both state and Commonwealth governments, and states have to draw up water management plans that are subject to approval by the authority.

The states are responsible for enforcing these plans and ensuring that allocations are not exceeded. The Murray-Darling Basin Authority cannot easily enforce action on the ground – a situation that generates potential for state-level political interference, as alleged by the Four Corners investigation.

4. Trust and transparency

The Murray-Darling Basin Plan was built on a foundation of trust and transparency. The buyback scheme has transformed water into a tradeable commodity worth A$2 billion a year, a sizeable chunk of which is held by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office.

Water trading has also helped to make water use more flexible. In a dry year, farmers with annual crops (such as cotton) can choose not to plant and instead to sell their water to farmers such as horticulturists who must irrigate to keep their trees alive. This flexibility is valuable in Australia’s highly variable climate.

Yet it is also true that water trading has created some big winners. Those with pre-existing water rights have been able to capitalise on that asset and invest heavily in buying further water rights, an outcome highlighted in the Four Corners story.

More than A$20 million in research investment has been devoted to ensuring that the ecological benefits of water are optimised – most notably through the Environmental Water Knowledge and Research and Long Term Intervention Monitoring programs. What is not clear is whether water extractions and their policing have been subjected to a similar degree of review and rigour.

What next for the Murray-Darling Basin?The public needs to be able to trust that all parties are working honestly and accountably. This is particularly true for the downstream partners, who are the most likely victims of management failures upstream. Without trust in the upstream states, the Murray-Darling Basin Plan will unravel.

State governments urgently need to reaffirm their commitment to the four pillars that underpin the Murray-Darling Basin Plan, and to reassure the public that in retaining control of water they are operating in good faith.

Finally, rigour and transparency are needed in assessing the Basin Plan’s methods and environmental benefits, and the operation of the water market. The Productivity Commission’s review of national water policy, and its specific review of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan next year, will offer a clear opportunity to reassure everyone that the A$13 billion of public money that has gone into water reform in the past decade has been money well spent.

Only then will the fragile trust that underlies the water reform process be maintained and built.

Ross Thompson receives funding from the Australian Research Council, and has previously been contracted to the NSW and Victorian state governments to provide advice on the MDB Plan. He has completed paid external reviews for the Murray Darling Basin Authority, and is a researcher on current projects funded by the Commonwealth Environment Water Holder.

Scientific integrity must be defended, our planet depends on it

To conserve Earth's remarkable species, such as the violet sabrewing, we must also defend the importance of science. Jeremy Kerr, Author provided

To conserve Earth's remarkable species, such as the violet sabrewing, we must also defend the importance of science. Jeremy Kerr, Author providedScience is the best method we have for determining what is likely to be true. The knowledge gained from this process benefits society in a multitude of ways, including promoting evidence-based decision-making and management. Nowhere is this more important than conservation, as the intensifying impacts of the Anthropocene increasingly threaten the survival of species.

But truth can be inconvenient: conservation goals sometimes seem at odds with social or economic interests. As a result, scientific evidence may be ignored or suppressed for political reasons. This has led to growing global trends of attacking scientific integrity.

Recent assaults on science and scientists under Donald Trump’s US administration are particularly extreme, but extend far more broadly. Rather than causing scientists to shrink from public discussions, these abuses have spurred them and their professional societies to defend scientific integrity.

Among these efforts was the recent March for Science. The largest pro-science demonstration in history, this event took place in more than 600 locations around the world.

We propose, in a new paper in Conservation Biology, that scientists share their experiences of defending scientific integrity across borders to achieve more lasting success. We summarise eight reforms to protect scientific integrity, drawn from lessons learned in Australia, Canada and the US.

March for science in Melbourne.

John Englart (Takver)

What is scientific integrity?

March for science in Melbourne.

John Englart (Takver)

What is scientific integrity?

Scientific integrity is the ability to perform, use and disseminate scientific findings without censorship or political interference. It requires that government scientists can communicate their research to the public and media. Such outbound scientific communication is threatened by policies limiting scientists’ ability to publish, publicise or even mention their research findings.

Public access to websites or other sources of government scientific data have also been curtailed. Limiting access to taxpayer-funded information in this way undermines citizens’ ability to participate in decisions that affect them, or even to know why decisions are being made.

News of the rediscovery of the shrub Hibbertia fumana (left) in Australia was delayed until a development at the site of rediscovery had been permitted. Political considerations delayed protection of the wolverine (right) in the United States.

Wolverine - U.S. National and Park Service. _Hibbertia fumana_ - A. Orme

News of the rediscovery of the shrub Hibbertia fumana (left) in Australia was delayed until a development at the site of rediscovery had been permitted. Political considerations delayed protection of the wolverine (right) in the United States.

Wolverine - U.S. National and Park Service. _Hibbertia fumana_ - A. Orme

A recent case of scientific information being suppressed concerns the rediscovery, early in 2017, of the plant Hibbertia fumana in New South Wales. Last seen in 1823, 370 plants were found.

Rather than publicly celebrate the news, the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage was reportedly asked to suppress the news until after a rail freight plan that overlapped with the plants’ location had been approved.

Protecting scientists’ right to speak outScientists employed by government agencies often cannot discuss research that might relate to their employer’s policies. While it may not be appropriate for scientists to weigh in on policy recommendations – and, of course, constant media commentaries would be chaos – the balance has tipped too far towards restriction. Many scientists cannot publicly refer to their research, or that of others, let alone explain the significance of the findings.

To counter this, we need policies that support scientific integrity, an environment of transparency and the public’s right to access scientific information. Scientists’ right to speak freely should be included in collective bargaining agreements.

Scientific integrity requires transparency and accountability. Information from non-government scientists, through submitted comments or reviews of draft policies, can inform the policy process.

Although science is only one source of influence on policy, democratic processes are undermined when policymakers limit scrutiny of decision-making processes and the role that evidence plays in them.

Let science inform policyIndependent reviews of new policy are a vital part of making evidence-based decisions. There is room to broaden these reviews, inviting external organisations to give expert advice on proposed or existing policies. This also means transparently acknowledging any perceived or actual vested interests.

Australian governments often invite scientists and others to contribute their thoughts on proposed policy. The Finkel Review, for example, received 390 written submissions. Of course, agencies might not have time to respond individually to each submission. But if a policy is eventually made that seems to contradict the best available science, that agency should be required to account for that decision.

Finally, agencies should be proactively engaging with scientific groups at all stages of the process.

Active advocacyStrengthening scientific integrity policies when many administrations are publicly hostile to science is challenging. Scientists are stuck reactively defending protective policies. Instead, they should be actively advocating for their expansion.

The goal is to institutionalise a culture of scientific integrity in the development and implementation of conservation policies.

A transnational movement to defend science will improve the odds that good practices will be retained and strengthened under more science-friendly administrations.

The monarch butterfly, now endangered in Canada, and at risk more broadly.

Jeremy Kerr

The monarch butterfly, now endangered in Canada, and at risk more broadly.

Jeremy Kerr

Many regard science as apolitical. Even the suggestion of publicly advocating for integrity or evidence-based policy and management makes some scientists deeply uncomfortable. It is telling that providing factual information for policy decisions and public information can be labelled as partisan. Nevertheless, recent research suggests that public participation by scientists, if properly framed, does not harm their credibility.

Scientists can operate objectively in conducting research, interpreting discoveries and publicly explaining the significance of the results. Recommendations for how to walk such a tricky, but vital, line are readily available.

Scientists and scientific societies must not shrink from their role, which is more important than ever. They have a responsibility to engage broadly with the public to affirm that science is indispensable for evidence-based policies and regulations. These critical roles for scientists help ensure that policy processes unfold in plain sight, and consequently help sustain functioning, democratic societies.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Carlos Carroll, a conservation biologist at the Klamath Center for Conservation Research.

Euan Ritchie receives funding from the Australian Research Council. Euan Ritchie is a Director (Media Working Group) of the Ecological Society of Australia, and a member of the Australian Mammal Society.

James Watson receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Jeremy Kerr receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through a Discovery Grant and Discovery Accelerator Supplement.

Martine Maron receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the National Environmental Science Programme, the Science for Nature and People Partnership, and the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. She is a Director of BirdLife Australia and a Governor of WWF Australia.

Who's afraid of the giant African land snail? Perhaps we shouldn't be

Giant African land snails can grow up to 15cm long. Author provided

Giant African land snails can grow up to 15cm long. Author providedThe giant African land snail is a poster child of a global epidemic: the threat of invasive species. The snails are native to coastal East Africa, but are now found across Asia, the Pacific and the Americas – in fact, almost all tropical mainlands and islands except mainland Australia.

Yet, despite their fearsome reputation, our research on Christmas Island’s invasive snail population suggests the risk they pose to native ecosystems has been greatly exaggerated.

Giant African land snails certainly have the classic characteristics of a successful invader: they can thrive in lots of different places; survive on a broad diet; reach reproductive age quickly; and produce more than 1,000 eggs in a lifetime. Add it all together and you have a species recognised as among the worst invaders in the world.

The snails can eat hundreds of plant species, including vegetable crops (and even calcium-rich plaster and stucco), and have been described as a major threat to agriculture.

They have been intercepted at Australian ports, and the Department of Primary Industries concurs that the snails are a “serious threat”.

Despite all this, there have been no dedicated studies of their environmental impact. Some researchers suggest the risk to agriculture has been exaggerated from accounts of damage in gardens. There are no accounts of giant African land snails destroying natural ecosystems.

Quietly eating leaf litterIn research recently published in the journal Austral Ecology, we tested these assumptions by investigating giant African land snails living in native rainforest on Christmas Island.

Giant African land snails have spread through Christmas Island with the help of another invasive species: the yellow crazy ant.

Until these ants showed up, abundant native red land crabs ate the giant snails before they could gain a foothold in the rainforest. Unfortunately, yellow crazy ants have completely exterminated the crabs in some parts of the island, allowing the snails to flourish.

We predicted that the snails, which eat a broad range of food, would have a significant impact on leaf litter and seedling survival.

Unexpectedly, the snails we observed on Christmas Island confined themselves to eating small amounts of leaf litter.

Author provided

Unexpectedly, the snails we observed on Christmas Island confined themselves to eating small amounts of leaf litter.

Author provided

However, our evidence didn’t support this at all. Using several different approaches – including a field experiment, lab experiment and observational study – we found giant African land snails were pretty much just eating a few dead leaves and little else.

We almost couldn’t distinguish between leaf litter removal by the snails compared to natural decomposition. They were eating leaf litter, but not a lot of it.

We saw almost no impact on seedling survival, and the snails were almost never seen eating live foliage. In one lab trial, we attempted to feed snails an exclusive diet of fresh leaves, but so many of these snails died that we had to cut the experiment short. Perhaps common Christmas Island plants just aren’t palatable.

It’s possible that the giant African land snails are causing other problems on Christmas Island. In Florida, for example, they carry parasites that are a risk to human health. But for the key ecological processes we investigated, the snails do not create the kind of disturbance we would assume from their large numbers.

We effectively excluded snails from an area by lining a fence with copper tape.

Author provided

We effectively excluded snails from an area by lining a fence with copper tape.

Author provided

The assumption that giant African land snails are dangerous to native plants and agriculture comes from an overriding sentiment that invasive species are damaging and must be controlled.

Do we have good data on the ecological impact of all invasive species? Of course not. Should we still try to control all abundant invasive species even if we don’t have evidence they are causing harm? That’s a more difficult question.

The precautionary principle drives much of the thinking behind the management of invasive species, including the giant African land snail. The cost of doing nothing is potentially very high, so it’s safest to assume invasive species are having an effect (especially when they exist in high numbers).

But we should also be working hard to test these assumptions. Proper monitoring and experiments give us a true picture of the risks of action (or inaction).

In reality, the giant African land snail is more the poster child of our own knee-jerk reaction to abundant invaders.

Luke S. O'Loughlin received funding from the Hermon Slade Foundation and the Holsworth Wildlife Endowment Fund

Peter Green receives funding from the Department of Environment and Energy and the Hermon Slade Foundation for this research.

Rising carbon dioxide is making the world's plants more water-wise

Land plants are absorbing 17% more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere now than 30 years ago, our research published today shows. Equally extraordinarily, our study also shows that the vegetation is hardly using any extra water to do it, suggesting that global change is causing the world’s plants to grow in a more water-efficient way.

Water is the most precious resource needed for plants to grow, and our research suggests that vegetation is becoming much better at using it in a world in which CO₂ levels continue to rise.

The ratio of carbon uptake to water loss by ecosystems is what we call “water use efficiency”, and it is one of the most important variables when studying these ecosystems.

Our confirmation of a global trend of increasing water use efficiency is a rare piece of good news when it comes to the consequences of global environmental change. It will strengthen plants’ vital role as global carbon sinks, improve food production, and might boost water availability for the well-being of society and the natural world.

Yet more efficient water use by the world’s plants will not solve our current or future water scarcity problems.

Changes in global terrestrial uptake of carbon dioxide, water use efficiency and ecosystem evapotranspiration during 1982-2011.

Boosting carbon uptake

Changes in global terrestrial uptake of carbon dioxide, water use efficiency and ecosystem evapotranspiration during 1982-2011.

Boosting carbon uptake

Plants growing in today’s higher-CO₂ conditions can take up more carbon – the so-called CO₂ fertilisation effect. This is the main reason why the terrestrial biosphere has taken up 17% more carbon over the past 30 years.

The enhanced carbon uptake is consistent with the global greening trend observed by satellites, and the growing global land carbon sink which removes about one-third of all CO₂ emissions generated by human activities.

Increasing carbon uptake typically comes at a cost. To let CO₂ in, plants have to open up pores called stomata in their leaves, which in turn allows water to sneak out. Plants thus need to strike a balance between taking up carbon to build new leaves, stems and roots, while minimising water loss in the process. This has led to sophisticated adaptations that has allowed many plant species to conquer a range of arid environments.

One such adaptation is to close the stomata slightly to allow CO₂ to enter with less water getting out. Under increasing atmospheric CO₂, the overall result is that CO₂ uptake increases while water consumption does not. This is exactly what we have found on a global scale in our new study. In fact, we found that rising CO₂ levels are causing the world’s plants to become more water-wise, almost everywhere, whether in dry places or wet ones.

Growth hotspotsWe used a combination of plot-scale water flux and atmospheric measurements, and satellite observations of leaf properties, to develop and test a new water use efficiency model. The model enables us to scale up from leaf water use efficiency anywhere in the world to the entire globe.

We found that across the globe, boreal and tropical forests are particularly good at increasing ecosystem water use efficiency and uptake of CO₂. That is due in large part to the CO₂ fertilisation effect and the increase in the total amount of leaf surface area.

Importantly, both types of forests are critical in limiting the rise in atmospheric CO₂ levels. Intact tropical forest removes more atmospheric CO₂ than any other type of forest, and the boreal forests of the planet’s far north hold vast amounts of carbon particularly in their organic soils.

Meanwhile, for the semi-arid ecosystems of the world, increased water savings are a big deal. We found that Australian ecosystems, for example, are increasing their carbon uptake, especially in the northern savannas. This trend may not have been possible without an increase in ecosystem water use efficiency.

Previous studies have also shown how increased water efficiency is greening semi-arid regions and may have contributed to an increase in carbon capture in semi-arid ecosystems in Australia, Africa and South America.

Trends in water use efficiency over 1982-2011.

CREDIT, Author provided

It’s not all good news

Trends in water use efficiency over 1982-2011.

CREDIT, Author provided

It’s not all good news

These trends will have largely positive outcomes for the plants and the animals (and humans) consuming them. Wood production, bioenergy and crop growth are (and will be) less water-intensive under climate change than they would be without increased vegetation water use efficiency.

But despite these trends, water scarcity will nevertheless continue to constrain carbon sinks, food production and socioeconomic development.

Some studies have suggested that the water savings could also lead to increased runoff and therefore excess water availability. For dry Australia, however, more than half (64%) of the rainfall returning to the atmosphere does not go through vegetation, but through direct soil evaporation. This reduces the potential benefit from increased vegetation water use efficiency and the possibility for more water flowing to rivers and reservoirs. In fact, a recent study shows that while semi-arid regions in Australia are greening, they are also consuming more water, causing river flows to fall by 24-28%.

Our research confirms that plants all over the world are likely to benefit from these increased water savings. However, the question of whether this will translate to more water availability for conservation or for human consumption is much less clear, and will probably vary widely from region to region.

Pep Canadell receives funding from the Australian National Environmental Science Program.

Francis Chiew works for CSIRO, which receives funding from the Commonwealth Government.

Lei Cheng works for CSIRO, which receives funding from the Commonwealth Government.

Lu Zhang works for CSIRO, which receives funding from the Commonwealth Government.

Ying-Ping Wang receives funding from the Australian National Environmental Science Program.

Australia’s new marine parks plan is a case of the Emperor's new clothes

Orca family group at the Bremer Canyon off WA's south coast. R. Wellard, Author provided

Orca family group at the Bremer Canyon off WA's south coast. R. Wellard, Author providedThe federal government’s new draft marine park plans are based on an unsubstantiated premise: that protection of Australia’s ocean wildlife is consistent with activities such as fishing and oil and gas exploration.

Under the proposed plans, there would be no change to the boundaries of existing marine parks, which cover 36% of Commonwealth waters, or almost 2.4 million square kilometres. But many areas inside these boundaries will be rezoned to allow for a range of activities besides conservation.

The plans propose dividing marine parks into three types of zones:

- Green: “National Park Zones” with full conservation protection

- Yellow: “Habitat Protection Zones” where fishing is allowed as long as the seafloor is not harmed

- Blue: “Special Purpose Zones” that allow for specific commercial activities.

Crucially, under the new draft plans, the amount of green zones will be almost halved, from 36% to 20% of the marine park network, whereas yellow zones will almost double from 24% to 43%, compared with when the marine parks were established in 2012.

The government has said that this approach will “allow sustainable activities like commercial fishing while protecting key conservation features”.

But like the courtiers told to admire the Emperor’s non-existent new clothes, we’re being asked to believe something to be true despite strong evidence to the contrary.

The Emperor’s unrobingThe new plans follow on from last year’s release of an independent review, commissioned by the Abbott government after suspending the previous network of marine reserves implemented under Julia Gillard in 2012.

Yet the latest draft plans, which propose to gut the network of green zones, ignore many of the recommendations made in the review, which was itself an erosion of the suspended 2012 plans.

The extent of green zones is crucial, because the science says they are the engine room of conservation. Fully protected marine national parks – with no fishing, no mining, and no oil and gas drilling – deliver far more benefits to biodiversity than other zone types.

The best estimates suggest that 30-40% of the seascape should ideally be fully protected, rather than the 20% proposed under the new plans.

Partially protected areas, such as the yellow zones that allow fishing while protecting the seabed, do not generate conservation benefits equivalent to those of full protection.

While some studies suggest that partial protection is better than nothing, others suggest that these zones offer little to no improvement relative to areas fully open to exploitation.

Frydenberg has pointed out that, under the new plans, the total area zoned as either green or yellow will rise from 60% to 63% compared with the 2012 network. But yellow is not the new green. What’s more, yellow zones have similar management costs to green zones, which means that the government is proposing to spend the same amount of money for far inferior protection. And as any decent sex-ed teacher will tell you, partial protection is a risky business.

What do the draft plans mean?Let’s take a couple of examples, starting with the Coral Sea Marine Park. This is perhaps the most disappointing rollback in the new draft plan. The green zone, which would have been one of the largest fully protected areas on the planet, has been reduced by half to allow for fishing activity in a significantly expanded yellow zone.

Coral Sea Marine Park zoning, as recommended by Independent Review (left) and in the new draft plan (right), showing the proposed expansion of partial protection (yellow) vs full protection (green).

From http://www.environment.gov.au/marinereservesreview/reports and https://parksaustralia.gov.au/marine/management/draft-plans/

Coral Sea Marine Park zoning, as recommended by Independent Review (left) and in the new draft plan (right), showing the proposed expansion of partial protection (yellow) vs full protection (green).

From http://www.environment.gov.au/marinereservesreview/reports and https://parksaustralia.gov.au/marine/management/draft-plans/

This yellow zone would allow the use of pelagic longlines to fish for tuna. This is despite government statistics showing that around 30% of the catch in the Eastern Tuna and Billfish fishery consists of species that are either overexploited or uncertain in their sustainability, and the government’s own risk assessment that found these types of fishing lines are incompatible with conservation.

What this means, in effect, is that the plans to establish a world-class marine park in the Coral Sea will be significantly undermined for the sake of saving commercial tuna fishers A$4.1 million per year, or 0.3% of the total revenue from Australia’s wild-catch fisheries.

Contrast this with the A$6.4 billion generated by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in 2015-16, the majority of which comes from non-extractive industries.

This same erosion of protection is also proposed in Western Australia, where the government’s draft plan would reduce green zones by 43% across the largest marine parks in the region.

Zoning for the Gascoyne Marine Park as recommended by the Independent Review (left) and the new draft plan (right).

http://www.environment.gov.au/marinereservesreview/reports and https://parksaustralia.gov.au/marine/management/draft-plans/

Zoning for the Gascoyne Marine Park as recommended by the Independent Review (left) and the new draft plan (right).

http://www.environment.gov.au/marinereservesreview/reports and https://parksaustralia.gov.au/marine/management/draft-plans/

Again, this is despite clear evidence that the fishing activities occurring in these areas are not compatible with conservation. Such proposals also ignore future pressures such as deep-sea mining.

The overall effect is summarised neatly by Frydenberg’s statement that the government’s plans will:

…increase the total area of the reserves open to fishing from 64% to 80% … (and) make 97% of waters within 100 kilometres of the coast open for recreational fishing.

Building ocean resilienceScience shows that full protection creates resilience by supporting intact ecosystems. Fully protected green zones recover faster from flooding and coral bleaching, have reduced rates of disease, and fend off climate invaders more effectively than areas that are open to fishing.

Green zones also contribute indirectly to the blue economy. They help support fisheries and function as “nurseries” for fish larvae. For commercial fisheries, these sanctuaries are more important than ever in view of the declines in global catches since we hit “peak fish” in 1996.

Of course it is important to balance conservation with sustainable economic use of our oceans. Yet the government’s new draft plan leaves a huge majority of Australia’s waters open to business as usual. It’s a brave Emperor who thinks this will protect our oceans.

So let’s put some real clothes on the Emperor and create a network of marine protection that supports our blue economy and is backed by science.

Jessica Meeuwig has received funding from the National Environmental Science Programme and the Ian Potter Foundation in relation to understanding offshore marine protected areas.

David Booth has received funding from the Australia Research Council. He is affiliated with Australian Coral Reef Society and Australian Marine Science Association

Hugs, drugs and choices: helping traumatised animals

Interspecies relationships can help traumatised animals form healthy attachments. Sugarshine animal sactuary, CC BY-SA

Interspecies relationships can help traumatised animals form healthy attachments. Sugarshine animal sactuary, CC BY-SARosie, like a real-life Babe, ran away from an organic piggery when she was only a few days old. She was found wandering in a car park, highly agitated, by a family who took her home and made her their live-in pet. However, after three months they could no longer keep her.

She was relocated to the Sugarshine animal sanctuary, outside Lismore in New South Wales. Kelly Nelder, Sugarshine’s founder and a mental health nurse, described her as “highly strung” and “needy”. It’s not surprising that Rosie, after the loss of two primary care attachments, was unable to bond with the other pigs; she was traumatised.

I met Rosie when I visited Sugarshine, investigating the similarities between human and animal trauma. I spent 20 years as a clinical and forensic psychologist, but as an undergraduate I studied zoology.

My zoology lecturers told us not to anthropomorphise – that is, not to project human qualities, intentions and emotions onto the animals we studied. But now there is a growing recognition of animals’ inner life and their experience of psychopathology, including trauma.

At Sugarshine, traumatised animals are given freedom to find solitude or company as they wish. Interspecies relationships are encouraged, like a baby goat being cared for by a male adult pig, or a rooster who sleeps alongside a goat.

Rosie has been at Sugarshine for a few months now and is more settled, roaming its gullies, farmyards and shelters, although according to Kelly she’s still anxious. She prefers the company of the bobby calves, wedging herself between them as they lie on the ground, getting skin-to-skin contact, falling asleep, and beginning the reattachment process.

Rosie the anxious pig likes to sleep with bobby calves at Sugarshine animal sanctuary.

Sugarshine animal sanctuary, CC BY

Understanding trauma in animals

Rosie the anxious pig likes to sleep with bobby calves at Sugarshine animal sanctuary.

Sugarshine animal sanctuary, CC BY

Understanding trauma in animals

I first made the connection between human and animal trauma on a visit to Possumwood Wildlife, a centre outside Canberra that rehabilitates injured kangaroos and abandoned joeys, wallabies and wombats. There I met its founders, economics professor Steve Garlick and his partner Dr Rosemary Austen, a GP.

When joeys were first brought into their care, Steve told me, they were “inconsolable” and “dying in our arms”, even while physically unharmed, with food and shelter available to them.

But this response made sense once they recognised the joey’s symptoms as reminiscent of post-traumatic stress disorder in humans: intrusive symptoms, avoidant behaviour, disturbed emotional states, heightened anxiety and hypervigilance.

Researchers at the University of Western Australia have developed non-invasive means for measuring stress and mood in animals and are now working with sheep farmers to improve the well-being of their animals. PTSD has been identified in elephants, dogs, chimpanzees and baboons, for example.

Safe, calm and caringTo rehabilitate from trauma, humans and animals need to feel safe and away from cues that trigger the individual’s threat response, deactivating the sympathetic nervous system (the fight-flight response). They also need a means of self-soothing, or to gain soothing from another, activating the parasympathetic nervous system (the rest, digest and calm response).

Progress, from then on, requires the development of a secure relationship with at least one other accepting and caring person or animal. Often, this “other” is someone new. In mammals, including us, this activates our affiliative system: our strong desire for close interpersonal relationships for safety, soothing and stability. We enter a calmer, receptive state of being so that the reattachment process can begin.

Possumwood uses three stages for trauma rehabilitation. Young animals are first kept in a dark, quiet environment indoors to reduce noises or sounds that might trigger their fight-flight response. Here they have the opportunity to develop new kin friendships of their own choosing.

Sedatives (Diazepam and Fluphenazine) are judiciously used in the early stages. Then, the principal carer spends as much time as possible feeding and caressing them to build a new bond.

Kangaroos are social animals, unable to survive in the wild unless part of a mob. So joeys are moved next to a large garage, and then finally to an outdoor yard, gradually being exposed to more kangaroos and creating social bonds. Once a mob grows to 30 or so healthy animals, they are released into the wild together.

The fundamentals are the sameThe similarity between animal and human trauma is not surprising. Mammalian brains (birds also appear to experience trauma) share the principal architecture involved in experiencing trauma. The primates, and certainly humans, have a greater capacity for cognitive reflection, which in my clinical experience can be both a help and a hindrance.

My observations of trauma rehabilitation at Sugarshine and Possumwood emphasises the universal fundamentals:

- A sense of agency (freedom and control over their choices)

- To feel safe

- To develop a trusting, caring bond with at least one other creature

- Reintegration into the community at the trauma sufferer’s own discretion.

For those experiencing social isolation and shame around their trauma – such as returned soldiers or the victims of domestic violence – these principles could not be more pertinent. And for our non-human cousins, like Rosie, we would do well to remember that they do feel, and they do hurt.

David John Roland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

In banning plastic bags we need to make sure we're not creating new problems

The recent decision by Australia’s big two supermarkets to phase out free single-use plastic bags within a year is just the latest development in a debate that has been rumbling for decades.

State governments in Queensland and New South Wales have canvassed the idea, which has been implemented right across the retail sector in South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory.

So far, so good. But are there any downsides? Many of you, for instance, face the prospect of paying for bin liners for the first time ever. And while that might sound tongue-in-cheek, it shows the importance of considering the full life-cycle of the plastics we use.

Pros and consOn a direct level, banning single-use plastic bags will avoid the resource use and negative environmental impacts associated with their manufacture. It will reduce or even eliminate a major contaminant of kerbside recycling. When the ACT banned these bags in 2011 there was a reported 36% decrease in the number of bags reaching landfill.

However, the ACT government also noted an increase in sales of plastic bags designed specifically for waste. These are typically similar in size to single-use shopping bags but heavier and therefore contain more plastic.

Ireland’s tax on plastic shopping bags, implemented in 2002, also resulted in a significant increase in sales of heavier plastic waste bags. These bags are often dyed various colours, which represents another resource and potential environmental contaminant.